Few Americans truly understand the racial schism separating white and black citizens. The visible success of Black Americans in business, sports, entertainment and politics makes it seem like there is more societal change than there really is, hiding the still powerful and enduring realities of systemic racism.

One could say, racism in America has become hypernormalized. That is, with the indisputable improvement in race relations, racism is neither easily discernable nor interpretable at the level of historic meaning. It is plausibly deniable and simply woven into the fabric of American life.

In 2008, Barack Obama swept to victory as America’s first Black president. This reduced perception of racism as it suggested we were headed toward being a post-racial society. In reality, Obama’s election entrenched racial resentment, as it overturned the country’s implicit racial hierarchy. White support for Congressional Democrats collapsed to its lowest level in the history of House exit polling.

At rallies for the Tea Party, people held signs saying things like “Obama Plans White Slavery.” Steve King, an Iowa congressman, complained that Obama “favors the black person.” Rush Limbaugh, bard of white decline, called Obama’s presidency a time when “the white kids now get beat up, with the black kids cheering.” Glenn Beck called the president’s health-care plan “reparations.”

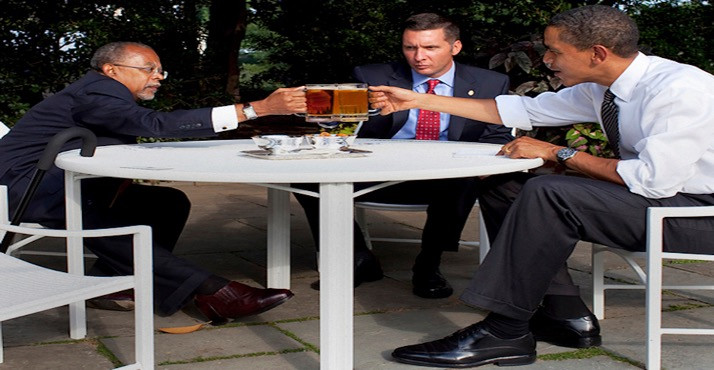

When, in July 2009, President Obama criticized the arrest of eminent Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. while he was trying to get into his own house, saying the officer had “acted stupidly,” a third of whites said the mild remark made them feel less favorably toward the president, and nearly two-thirds claimed that Obama had “acted stupidly” by commenting.

Former president Jimmy Carter remarked, “An overwhelming portion of the animosity toward President Obama is due to the fact that he is a black man. That racism inclination still exists.” The furor grew so great that the president had to apologize to the police officer and invited him and Gates to the White House for a “beer summit” to convey a hopeful message about race relations in this country.

Researchers Josh Pasek, Jon Krosnick, and Trevor Tompson found the proportion of people in 2008 expressing anti-black attitudes was 31 percent among Democrats, and 71 percent among Republicans. In 2012, 32 percent of Democrats held anti-black views, while 79 percent of Republicans did.

Source: Associated Press

In June 2013, the Supreme Court’s controversial decision in the Shelby County v. Holder case gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This was the landmark legislation passed during the civil rights movement that prohibited racial discrimination in voting. The ruling invalidated the Section 5 preclearance system, the center piece of the law, which required states with a history of voting discrimination to approve their elections or voting laws changes with the federal government.

In her dissent, Justice Ruth Ginsburg said Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy and the nation’s commitment to justice had been “disserved.” Civil rights leader John Lewis, who was brutally beaten marching for the right to vote in Selma in 1965, said that the Supreme Court “stuck a dagger into the heart of the Voting Rights Act.”

What a tryst with history! The Reconstruction Act of 1867 granted voting rights to African Americans following the turbulent Civil War. Black voter turnout neared 90 percent in many jurisdictions. Newly enfranchised blacks gained a political voice for the first time in US history, winning election to southern state legislatures and even to Congress.

Then came the Compromise of 1877, an agreement brokered by Congress and the Supreme Court to settle the result of the disputed 1876 election. Republican Rutherford Hayes would become president if he promised to withdraw federal troops in the South and end Reconstruction.

It was the presence of federal troops that ensured the implementation of Reconstruction measures and held back some of the violence and political suppression of Blacks by those intent on restoring white supremacist rule. Thus began the intentional purging of Black people as eligible voters.

“They are to be returned to a condition of serfdom. An era of second slavery,” proclaimed Reconstruction-era governor Ames of Mississippi. “The political death of the negro will forever release the nation from the weariness from such political outbreaks.”

All eleven former Confederate states rewrote their constitutions to include provisions restricting voting rights with poll taxes, literacy tests, and felon disenfranchisement. From about 1900 to 1965, most Black Americans were not allowed to vote in the South.

Armed with this historical insight, achieving the once unthinkable prospect of having a Black president in the White House was not a sign of racial progress. On the contrary, President Obama was a “political outbreak” and America needed to return to its supremacist roots.

The Shelby County decision opened the floodgates to new laws restricting voting throughout the country, including registration restrictions, early voting cutbacks, and strict photo ID requirements that millions of citizens don’t have. This, by design, made voting harder for people of color.

In North Carolina, Republican lawmakers requested racial breakdowns of different voting methods, then crafted a bill that would “target African-Americans with almost surgical precision,” a federal judge wrote.

The 2016 election was the first presidential contest in 50 years without the full protections of the Voting Rights Act. States with new voting restrictions had 70 percent of the electoral votes needed to win the election. Counties that were freed from federal oversight saw minority voter turnout drop more sharply than it had in decades.

The stage was set for a new era of white hegemony.

Source: Supreme Court Building

The Black Lives Matter movement was founded in July 2013 after the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager. Incidentally, this was a month after the Supreme Court’s negation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

While noble in its objective, we believe the Black Lives Matter movement was misguided from the very beginning. It took attention away from what was happening in the courts and criminal justice system—the systematic exclusion and suppression of Black voters—and galvanized the country on the singular problem of combatting police brutality.

The movement gathered momentum after the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of the police in 2014. There was outrage over a pattern of police brutality against young black men. Amid public outcry and violent unrest, President Obama convened the White House Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

In April 2015, based on scores of interviews with law-enforcement professionals, criminal justice researchers, academics and civic leaders, the task force presented its report. Their notion was for law enforcement to be “guardians of the community and not an occupying force” to co-produce public safety. Obama discussed its potential transformative impact on the field. There was hope this would serve as a catalyst for the type of police reform needed in communities across the country.

A year later, only 15 police departments had signed on to implement the task force’s reforms out of 18,000 state and local law-enforcement agencies. Because of a decentralized police system, it is a challenge to enforce top-down change. According to Barry Friedman, a professor of law and the director of the Policing Project at NYU School of Law, “When it comes to policing, the ordinary rules of democratic governance seem to evaporate.” American policing is impervious to reform.

About 1,000 times a year, a police officer shoots and kills someone while on duty. Yet, between 2005 and 2017, only 82 police officers across the country were charged with murder or manslaughter for an on-duty shooting. In that period, only 19 officers were convicted, and mostly for lesser manslaughter charges.

Efforts to hold problem officers accountable has faced resistance from powerful unions and sympathetic jurors. The Supreme Court has deftly avoided telling police officers what they can and cannot do when they use force.

This would be surprising unless we consider America’s biography. When the Reconstruction-era ended, lynchings unleashed terror on the Black population and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. The ratio of Black lynching victims to white lynching victims increased to more than 17 to 1 after 1900, from 6 to 1 before. In 99 percent of lynching cases the perpetrators escaped punishment.

Throughout this campaign of racial terrorism, Congress considered nearly 200 anti-lynching bills but failed to enact any legislation. Southern states protested federal interference in local affairs and passed their own anti-lynching laws to demonstrate that federal legislation was unnecessary but refused to enforce them. Black lives literally did not matter. Lynching is still not a federal crime.

“Even a black president could not untangle racism’s Gordian knot on the body politic,” said Peniel Joseph, professor of history at the University of Texas, reflecting on the limitations of Obama’s presidency in uplifting black America. “No one person—no matter how powerful—can single-handedly rectify structures of inequality constructed over centuries.”

Source: Getty Images

On February 23, Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old black jogger, was chased through the streets in Georgia by a white father and son and shot to death. The father is a former officer with the local police department. Both men were free until the video went viral on May 5.

On March 13, Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old black medical worker, was gunned down in her home in Louisville. The police officers who shot her eight times haven’t been charged or even put on administrative leave.

And then, on May 25, curbside in Minnesota during broad daylight, officer Derek Chauvin, with has hands in his pockets, casually kneeled on George Floyd’s neck until every last breath was forced out of his body. It took eight minutes and forty-six seconds. The public watched. That constitutes a lynching in the modern sense.

The head of the Minneapolis police union, Bob Kroll, who has a long disciplinary record and history of discrimination, said that the four police officers involved in the death of George Floyd, including Derek Chauvin, were improperly fired and that he would “fight for their jobs.”

Last fall, Kroll stood onstage with Trump at a campaign rally and praised the president for liberating his officers. “The Obama administration and the handcuffing and oppression of police was despicable,” Kroll told the crowd, clad in a red “Cops for Trump” t-shirt. He has referred to the Black Lives Matter as a “terrorist organization.”

President Trump ended the restriction on transferring military equipment to police and scrapped the use of consent decrees, a key federal tool for imposing accountability on police forces engaging in racial discrimination. The Trump administration basically freed local police departments from federal oversight. The Justice Department said that states are “a separate sovereign” with “special and protected roles.”

Minneapolis police chief, Medaria Arradondo, announced that he would withdraw from union contract negotiations in an effort to kickstart reform. But it would be naive to believe that Chauvin will be convicted for the killing of George Floyd. His acquittal would reveal, more than anything, the great power of white privilege.

Photo: Shutterstock