The Speaker takes us through the agricultural cycle and what it means for prices in grain markets.

The grain markets, especially corn and soybeans, are highly correlated. This is because the demand for corn and soybeans come from the same sectors—biofuels and meat. On the supply side, if one is overpriced versus the other, acreage for the next crop cycle will switch from one to the other. Wheat is a little less correlated as it is mainly a food grain that can work into the feed (meat) sector if there is a shortage of corn.

Autumn through the first half of the calendar year is when the bulk of the global corn, wheat and soybean crops are grown. With multiple stages in the production cycle—such as planting (do all the acres go in), stands (do the crops get well established in the soil), pollination (how many kernels of corn per plant), and filling (how heavy do the corn kernels and bean pods get)—and multiple winter and spring production cycles to get through in the US, South America and the Black sea, there are plenty of things that can go wrong in the growing season.

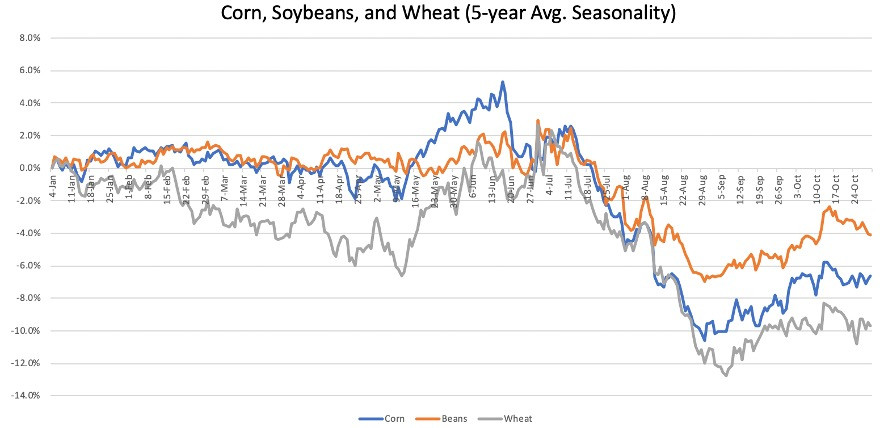

“That’s why grains tend to rally at some point during the growing season as there is always a weather-driven production scare somewhere,” the Speaker notes. “By the time we get to July, most of the production risks are known and priced.” Once the market realizes that a true crop shortage is unlikely—in part driven by the more weather-resilient seed technology—prices fall sharply. Then grain markets bottom sometime early autumn as the production cycle starts again.

Source: Bloomberg

The Speaker expects the above paradigm will repeat this year. He is looking to short grains over June.

The total corn supply is forecast at a record 18.1 billion bushels, up 14 percent year on year. But the historic low prices of ethanol may keep corn demand low. Brazil’s soybean production is expected to reach a record 125 million metric tons, up 9 percent year on year. The weaker Brazilian real is helping farmer production margins as they earn in dollars, which leads to more planted acreages.

“Could the massive swarms of locusts sweeping across South Asia, the Middle East and the Horn of Africa impact this cycle?” a participant asked. “Not quite,” said the Speaker. He noted that both Africa and India are not major producer of grains. “Crops are also not at the stage of the cycle where they would get hurt.”

Another participant posed a question about rising farmer bankruptcies, which jumped 20 percent in 2019 to an 8-year high.

“What you are seeing is farms with marginal acres where yields are a bit lower, and who are exposed to slightly higher input costs, are getting edged out of the market and the acres are potentially being consolidated,” said the Speaker. “But overall acreage and production has been very robust as long as weather has permitted.”

He noted that the first sign of a structural bull market in grains would be for acres to become unviable and not get planted—and that hasn’t happened. “If we stay at these low prices in corn, the next production cycle could get impacted, but it’s just early for that.”

Photo: Shutterstock