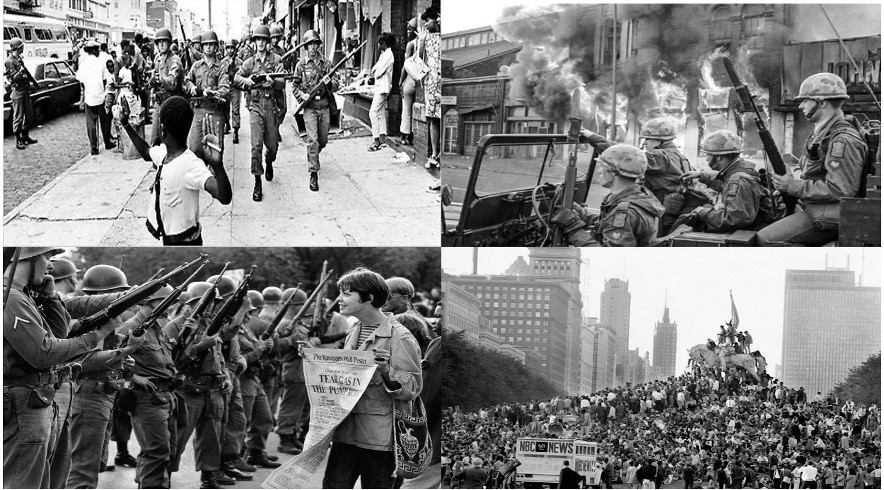

“There are too many things we do not wish to know about ourselves,” James Baldwin wrote, in 1963. Five years later, America would come to know the meaning of these words.

In July 1967, President Lyndon Johnson established the Kerner Commission to study the surge of Black urban uprisings. Until the early 1960s, race riots were ubiquitously white terror campaigns against Black people, which never led to any comparable study. The investigation was to understand the Black people’s problem.

Seven months later, rather than sanitize America’s ugly racial realities, the commission delivered an unflinching indictment of “white racism” as the fundamental cause of urban unrest. The rioting, the report said, was “in large part the culmination of 300 years of racial prejudice.”

What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it. Most Americans know little of the origins of the racial schism separating our white and Negro citizens. Few appreciate how central the problem has been to our social policy. Fewer still understand that it can be solved only if white Americans comprehend the rigid social, economic and educational barriers that have prevented Negroes from participating in the mainstream of American life.

Source: Getty Images

The commission called for far-reaching reforms in housing, education, employment, and policing, to prevent America becoming “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” Martin Luther King Jr. pronounced the report a “physician’s warning of approaching death, with a prescription for life.”

President Johnson was infuriated. Instead of considering the full weight of white prejudice, he canceled the White House ceremony to accept a bound copy of the report from his hand-picked panel, refused to sign customary letters recognizing the commissioners for their service, and avoided public commentary on the matter. As Shakespeare once said, “Few love to hear the sins they love to act.”

The main recommendations of the Kerner Commission were effectively shelved. A grim, 176-page report titled, The Harvest of American Racism, authored by the commission, and found later in the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library archives, had the word “Destroy” hastily scrawled out in green ink.

The report warned, in stark terms, that America stood on the “brink of race war.” The authors foresaw “the beginnings of guerilla warfare of black youth against white power in major cities” as armed white vigilantes rally behind overstretched police forces. In time, “we will in fact see civil war in the streets” with young black people “preferring to die on their feet than living on their knees.” Government would seek to impose mass repression, involving the suspension of civil liberties, as America becomes “a garrison state.” The stakes could not be higher: “The history of Algeria or Cyprus could be the future history of America.”

A month later, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down on a Memphis balcony. The nation engulfed in violent protests from coast to coast.

“What did you expect?” President Johnson told an aide. “I don’t know why we’re surprised. When you put your foot on a man’s neck and hold him down for 300 years, and then you let him up, what’s he going to do? He’s going to knock your block off.”

In many instances, the National Guard was required to quell the violence. In Washington, Chicago and Baltimore, it took tens of thousands of army soldiers and Marines. When the riots were over, some 39 people were dead, more than 2,600 injured and 21,000 arrested.

Source: Getty Images

According to Clay Risen, author of the book, A Nation in Flames: America in the Wake of the King Assassination, “the riots gave impetus to a new domestic militarism that saw the ghetto as an alien entity within American borders, a cancer that had to be isolated from the rest of the body public.”

President Nixon, who pledged “law and order” in his election campaign, used that revulsion to cut funds for housing support, small business loans, inner-city schools, and job training. Instead, he funneled money to police departments to buy anti-riot weaponry: body armor, tear gas, even surplus tanks. Nixon disparaged the Kerner Commission’s repeated emphasis on the role of police brutality in alienating Black citizens. He, and subsequent presidents, stood for semi-militarizing policing programs.

“By the early 1970s,” Risen wrote, “an anti-riot urban infrastructure was in place, one that psychologically, bureaucratically and even physically severed the ghetto from the rest of the city, and the city in turn from the suburbs.”

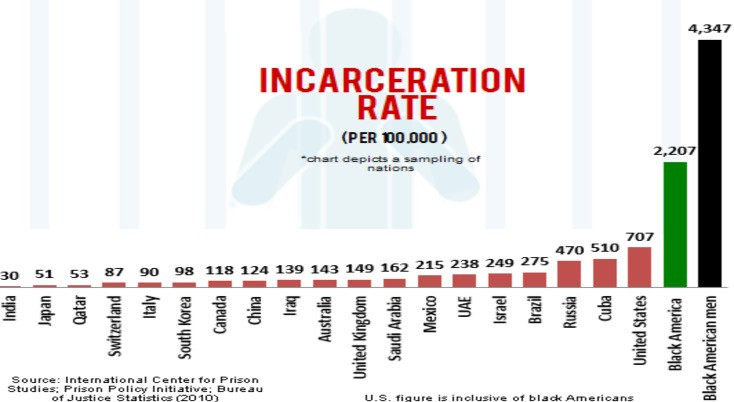

Not coincidentally, America’s incarcerated population began to rise rapidly. The Reagan administration’s sensationalized “War on Drugs” in the 1980s led to the hyper-criminalization of blackness. Discriminatory enforcement of drug laws—aggressively targeting drug use in black communities despite similar levels of drug use in white society—caused incarceration of legions of black men.

By 1990, for every 100,000 white Americans, 289 were in jail or prison; for every 100,000 black Americans, 1,860 were in jail or prison.

A 1994 federal crime bill to “Make America Safer,” signed by President Clinton, ushered another wave of intensified policing and harsher sentences that fueled mass incarceration, even though violent crimes began to drop in the early 1990s. America’s prisoner population exploded to 2 million by the turn of the century, from 300,000 in 1982. The population of US prisons today totals 2.3 million.

Source: Getty Images

America incarcerates more people than any country in the world, including repressive regimes like China and Russia. The US has 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prisoners.

What comes as a shock is realizing America imprisons a larger share of its black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid. One in three Black men can expect to spend time in prison during their lifetime. The incarceration rate for Blacks is six times the rate for whites and they receive longer sentences for the same crime. Black Americans are a much higher share of the prison population, 33 percent, than their 13 percent share of the US population.

What we are seeing is the political disempowerment of Black people. Most states block people with criminal records from voting in some way. More than 20 percent of Black voters in Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia are legally banned from voting. In 2016, 7.4 percent of the Black voting-age population was disenfranchised.

“Slavery is not abolished until the Black man has the ballot,” abolitionist movement leader Frederick Douglass famously said in 1865, a month after the Civil War ended. Some 4 million enslaved Black men, women and children had been granted their freedom.

Early in 1866, Congress passed the Civil Rights Bill, which gave Black Americans the rights of citizens. The 15th Amendment stated that voting rights could not be “denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

What happened next has parallels in the present. State legislatures passed discriminatory criminal laws or “black codes,” which created new criminal offenses such as “vagrancy” and “loitering.” This led to the mass arrest and incarceration of Black people. Private planters and business owners would then lease Blacks as prison laborers.

Essentially, the solution to re-enslave the Black population had become criminalization. And the criminal justice system became the central institution for sustaining racial hierarchy in America. There are tragic echoes of that history in our own time.

Looking at the sheer number of Black Americans damaged today by mass incarceration relative to the total population makes it hard to view it strictly through any other lens than racial control. A white dominance first achieved through slavery and continued through convict leasing was still attained through a racialized War on Drugs and “tough on crime” policies.

Source: The Sentencing Project

In The New Jim Crow, a book about racial disparities in the criminal justice system, Michelle Alexander explains this systematic effort to subjugate the Black minority.

Rather than rely on race, we use our criminal justice system to label people of color “criminals,” and then engage in all the practices we supposedly left behind. Today, it is legal to discriminate against criminals in nearly all the ways that it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans. Once you’re labeled a felon, the old forms of discrimination—employment and housing discrimination, denial of the right to vote, denial of educational opportunity, denial of food stamps and other public benefits, and exclusion from jury service—are suddenly legal.

This is the current state of Black America.

The typical Black household earns a fraction of white households—just 59 cents for every dollar. The gap between black and white annual household incomes is about $29,000 per year. Black Americans are over twice as likely to live in poverty as white Americans. Black children are three times as likely to live in poverty as white children.

Persistent segregation created large disparities in the quality of secondary education, leading to worse economic outcomes. Over the past 50 years, the unemployment rate for blacks has consistently approximated twice that of whites. Even in a strong economy, the labor market for black Americans is what white Americans experience during a recession.

The median net worth of white families is $171,000. That’s 10 times the median net worth of black families, which is only $17,100. A 2019 study found that over 97 percent of respondents estimated that the gap to be 80 percentage points smaller than the actual divide.

A college education does not help decrease the wealth gap. The median net worth of college-educated black families is $68,200, while it is $399,000 for white families. Just 42 percent of black families own their homes, compared to nearly three-quarters of white families.

There are deep inequities across nearly every social and economic indicator. As Theodore Johnson put it, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, “Black America is a fragile state embedded in the greatest superpower the world has ever known.”

Photo: Julio Cortez