The private equity (PE) industry is bracing for a difficult time in the wake of the sudden and unpredictable economic shock from Covid-19. Businesses backed by PE employ around 8.8 million people at over 35,000 companies, and account for 5 percent of America’s GDP. Seventy percent of those businesses have debt rated below investment grade, which puts them at greater risk in the post-virus economy.

Leveraged buyouts (LBO) are a key mechanism by which PE firms acquire portfolio companies. This practice has in part led to a wave of high-profile retail bankruptcies because companies were saddled with a huge amount of debt. PE-owned retailers have laid off nearly 600,000 workers over the past decade, even as the industry as a whole added 1 million jobs. This is not good Karma.

According to Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, “There’s this idea that Amazon disrupted retail, but retail is constantly being disrupted. The difference with private equity is that traditionally retail is low debt, which gives them breathing room. It’s not that they didn’t know to do e-commerce, they had no resources.”

A prominent example is Toys “R” Us. The retailer had a debt load of $1.86 billion in 2005 before PE firms swooped in with a leverage buyout that dumped more than $5 billion in debt. Sales held relatively steady but annual interest expense of $450 million consumed 97 percent of the company’s operating profit. The PE owners were raking millions a year in “advisory fees” for unspecified services rendered.

Eventually, Toys “R” Us succumbed to its debt burden, leading to the biggest bankruptcy of a retailer since Kmart in 2004, despite having 20 percent market share of all toys sold in America.

Source: Shutterstock

In a 1993 paper titled, “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit,” economists George Akerloff and Paul Romer explained how PE profits by destroying companies. They described a “looting strategy,” which basically amounted to a sophisticated laundering of assets and debts. A popular tactic is the use of “dividend recapitalizations,” adding new debt onto a portfolio company to give shareholders or limited partners an early payout.

Take Sycamore Partners, which took Staples private for $6.9 billion in 2017, putting $1.6 billion of its own money into the deal and layering $5.4 billion of loans. Sycamore paid itself a $300 million payment and then a $1 billion special dividend, one of the largest debt-funded dividends in history. But that is not all. The PE firm had Staples gift its $150 million, 650,000-square-foot headquarters in the Boston suburbs to a Sycamore affiliate. After which Staples signed a $135 million ten-year agreement to lease the property back “at market rent.”

According to Matt Stoller, author of the forthcoming book Goliath: The Hundred-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy, the game invented in the 1980s by Michael Milken has been institutionalized in ways that are hard to conceptualize.

PE firms use the same rationale as raiders did in the 1980s. They market themselves as helping to restructure companies to make them better run, getting the company away from the public markets where investor scrutiny prohibits executives from focusing on long-term value creation. It is a far more refined public relations operation, less openly piggish than the 1980s ‘greed is good’ model. There’s quasi-utopian rhetoric and Ivy encrusted elitism involved; Yale endowment chief David Swensen, a key validator for private equity investors, calls this model a “superior form of capitalism.”

Last year, PE funds in the US attracted a record $300 billion from investors. Over half of all capital raised was across $5 billion plus-sized funds, the first time since 2007.

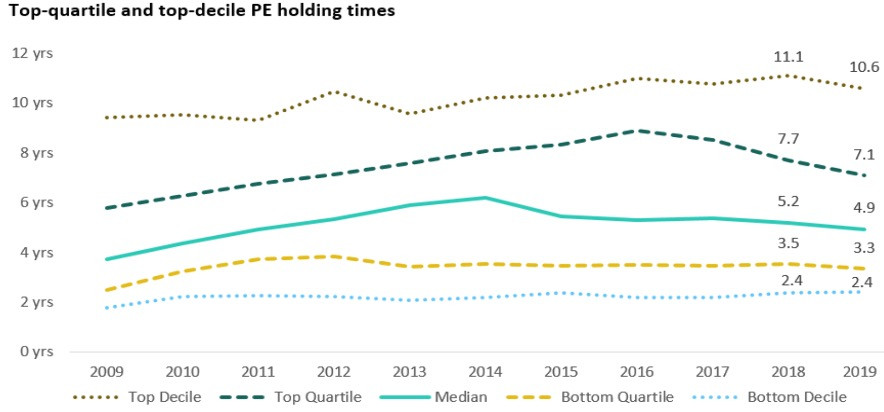

The myth is that PE is focused on the long-term value creation opportunity, with a determined focus on cash flow and margin improvement. And yet, the median PE holding period was 4.9 years in 2019 (below the peak of 6.2 years in 2014), and multiple expansion has been the main driver of returns since 2010, accounting for nearly half of the increase in enterprise value (EV), surpassing revenue growth or margin expansion.

Source: Pitchbook

Moody’s tracked 309 PE–backed companies from 2009 to 2018 and found that only 12 percent had been upgraded, whereas 32 percent had been downgraded “mainly because they failed to improve financial performance as projected at the time of the LBO or experienced deteriorating credit metrics and weakening liquidity.”

Over the 2016-2018 period, S&P Global Ratings found that EBITDA for PE–owned companies came in an average of 35 percent lower than projected at the time of the transaction, with a third missing by 50 percent or more. Zero percent exceeded projections in 2017, and only 6 percent managed to surpass them in 2018. The study discovered that almost half of earnings projected in LBOs stemmed from profit-inflating “add-backs”—adjustments made to account for expected cost savings or an anticipated rise in revenue—which was an “artificial deflation of leverage.”

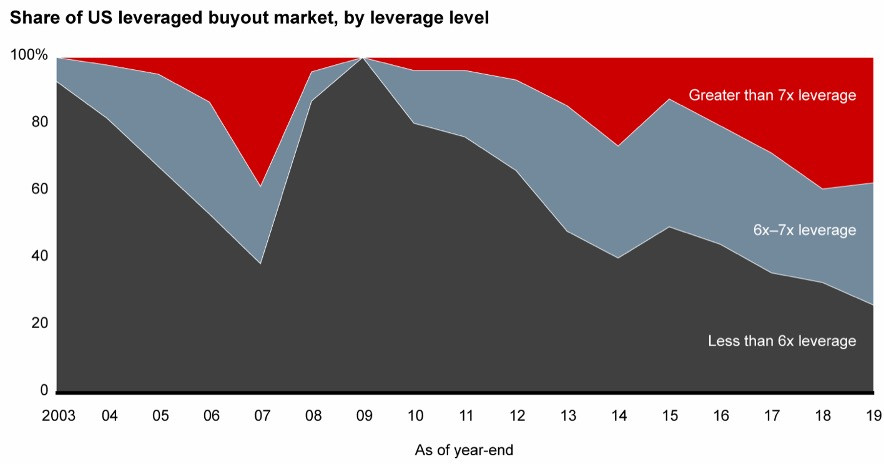

PE firms have been aggressively using debt, which provides financing and tax advantages, to just pay higher and higher prices for increasingly worse companies. Average deal valuations reached about 12x adjusted EBITDA before the pandemic, much higher than the previous peak of 9.7x in 2007. Deals with debt multiples higher than 6x EBITDA rose to more than 75 percent of the total. For the first time, the majority of PE capital went to companies that were unprofitable in 2019, according to data from Empirical Research Partners.

Most PE-backed companies tend to fall into the single B ratings category and 80 percent of all companies rated B3 are backed by private equity. According to Moody’s, about 30 percent of B-rated issuers default in a typical recession.

Source: Bain & Company

The federal loan program overseen by the Small Business Administration amid the destructive pandemic excludes loaning money to mom-and-pop businesses controlled by large parent companies—including PE firms. However, the PE industry, one of the wealthiest in America with a record $1.5 trillion cash on hand, is lobbying to waive those rules as well as keep carried interest in play.

Apollo’s co-founder Mark Rowan sent an email to Jared Kushner and other Trump administration policymakers seeking to relax rules on coronavirus relief moneys. “There has been no MORAL HAZARD. We have a totally unique situation,” wrote Rowan. There is no regret of past misdeeds. Negative karma creates negative results, which causes more negative actions, turning into a vicious cycle.

Apollo, KKR and Carlyle Group took over from banks as major lenders to midsize businesses after the global financial crisis, touting an extremely attractive investment opportunity to yield-hungry investors. This hot new asset class grew from $109 billion in 2010 to a staggering $261 billion in 2019. Banks found this type of lending (sub-investment-grade loans) to be unprofitable and government regulators warned that it posed a systemic risk to the economy. Now PE firms are bearing the brunt of the crisis with their exposure to the riskiest parts of the corporate credit market.

KKR has told investors that economic disruption is undermining the value of its funds and businesses: “Some portfolio companies in sectors such as health care, travel, entertainment, senior living and retail could become insolvent if the shutdowns aren’t ended.” The pandemic has exposed this better form of capitalism.

From 2010 to 2019, the dollar amount of private equity commitments increased fivefold on the promise of superior returns. But PE funds in the US have failed to outperform public markets for at least 14 years, while still earning more than $230 billion in management fees. A new study from Oxford University found US public pension funds earned average annual returns of 11 percent after fees in PE over the past 25 years, about the same return as small- and midcap US stock-market indexes.

“The time has come for scrutiny on private equity managers whose behavior serves their own interest first,” according Ted Seides, host of the Capital Allocators podcast. “How they conduct themselves through this period may prove one of the key attributes that determines their future.”

To quote writer Elbert Hubbard, “Men are not punished for their sins, but by them.”

Photo: Forbes