Inflation is the market’s number-one risk according to Bank of America’s monthly survey of global asset managers, displacing Covid-19 for the first time since February 2020. A net 93 percent of investors in the survey expect inflation to rise in the next twelve months, the highest reading in the history of the survey, which dates back to 1995.

What everyone sees is the unprecedented speed and scale of the fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic. Year-on-year growth in the monetary base is seven times larger than the peak during the Great Recession. As the American public emerges from the pandemic fully vaccinated and cashed-up, inflationary consequences will become evident, the thinking goes.

Harvard professor Lawrence Summers says the $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus risks triggering “inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation.” And this is without the potential rollout of President Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan. That’s at least another $3 trillion to be spent over ten years on infrastructure and strategic industries.

Starting next month, core PCE inflation could be expected to push above the 2 percent mark due to base effects from last year when the economy was shut down. After this burst of transitory inflation, everything we see at a micro level points to a more subdued inflation outlook than a durable shift above target in the inflation trend.

To learn more about how inflation will evolve, we must first understand the dynamics of inflation before the pandemic started. A sober reading of the data may reveal more than beguiling storytelling.

Food Prices

Food inflation was 0.9 percent in 2019 and has averaged 2 percent over the last twenty years. In 2020, food prices soared 3.5 percent because of disruptions due to the lockdown. Demand for food consumed at home increased as dining out ceased, while slaughter-plant closures caused a sharp jump in meat prices.

Food inflation has since come down and will likely return to the lower rates of inflation that preceded the pandemic. In 2021, food-at-home prices are expected to increase between 1 and 2 percent, and food-away-from-home prices are expected to increase between 2 and 3 percent.

The IMF examined the behavior of inflation around previous epidemics, weather-related events and natural disasters. What they found was a short-lived spike in inflation, driven by food prices, followed by a reversal to pre-epidemic levels.

Healthcare Services

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, it was against a backdrop of decades of rapid growth in healthcare spending. The ACA reduced Medicare overpayments to private insurers and medical providers and reduced the rate of hospital readmissions. This contributed to healthcare services inflation growing at less than half the long-term historical average rate and about a percentage point more slowly than the most recent historical period. Healthcare services inflation averaged 1.2 percent between 2014 and 2018.

The pandemic boosted healthcare inflation due to temporary measures such as add-on payments for Covid-19 treatments. With these policies likely to expire at the end of this year, the opposite effect will materialize in 2022. The ACA remains an important restraining force on overall healthcare inflation. A possible expansion under the Biden administration would exert additional downward pressure on healthcare service prices.

Source: Chicago Fed

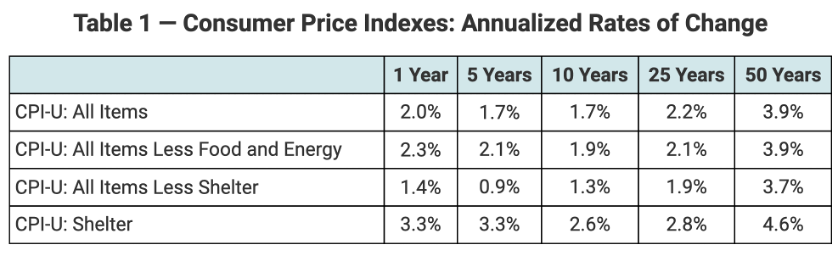

Shelter Costs

Prior to the pandemic, the cost of housing services, or shelter, was the most persistent contributor to inflation, averaging over 3 percent a year. If the cost of shelter is excluded, inflation was running well below the Fed’s 2 percent target. Consumer price inflation excluding shelter was only 1.4 percent in 2019 and 0.9 percent during the previous five years.

The eviction moratorium and rent forgiveness in 2020 dragged shelter inflation to a decade-low of 1.3 percent. Research from Moody’s Analytics and the Urban Institute estimates 9.4 million US renter households owe an average of $5,586 in back rent, utilities and related late fees as of January, for a total burden of $52.6 billion.

While homeowner demand is strengthening, rents are softening since the pandemic hit because of the negative employment impact. Average rents in 30 core American cities dropped more than 5 percent. In the New York area, apartment vacancies could rise as high as 6 percent, eclipsing the 3.6 percent vacancy rate at the height of the Great Recession.

Shelter costs should normalize, but we are unlikely to see the heady days of rent inflation prior to the pandemic. If shelter inflation returns to its historic average, adding about 0.2 percentage points to the overall consumer price index instead of about 0.8 percentage points during the last five years, core PCE inflation is unlikely to overshoot 2 percent.

Combined, healthcare and shelter account for slightly under half of the core PCE basket.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Employment Anomaly

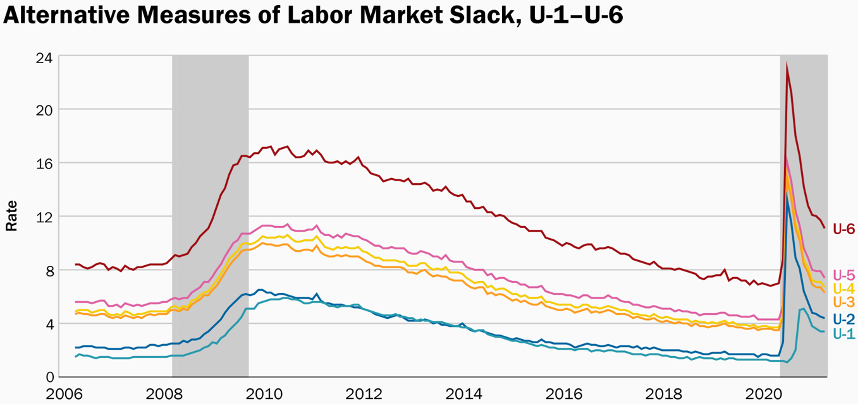

Various research studies have concluded that labor-market slack is a key reason for the persistent shortfall in inflation relative to the Fed’s 2 percent inflation goal. This pattern holds across recent decades in the US data.

For ten years after the onset of the Great Recession, inflation remained muted. Only when the unemployment rate declined to a 49-year low in 2018 did core PCE finally hit 2 percent. Wages were growing at the fastest pace since 2009.

At 6.2 percent, the unemployment rate is well above its pre-crisis level of 3.5 percent. Accounting for the number of people who have dropped out of the labor force entirely from a year ago, however, a truer measure of unemployment is likely closer to 10 percent. The pandemic has led to the largest twelve-month decline in labor-force participation since at least 1948. More people in America are out of work today than during the worst point of the Great Recession.

As we have noted in the past, it’s taking longer for employment to recover after each downturn. It took 30 months and 48 months, respectively, to regain jobs after the 1990 and 2001 recessions. It took 76 months after 2008. It’s possible that employment levels do not fully recover from the pandemic this decade.

While the Fed’s new mission of achieving “maximum employment” is a noble pursuit, it is also an unrealistic one. Since the 1970s, the US has never managed to recoup the manufacturing jobs lost in each recession.

Source: Brookings Institution

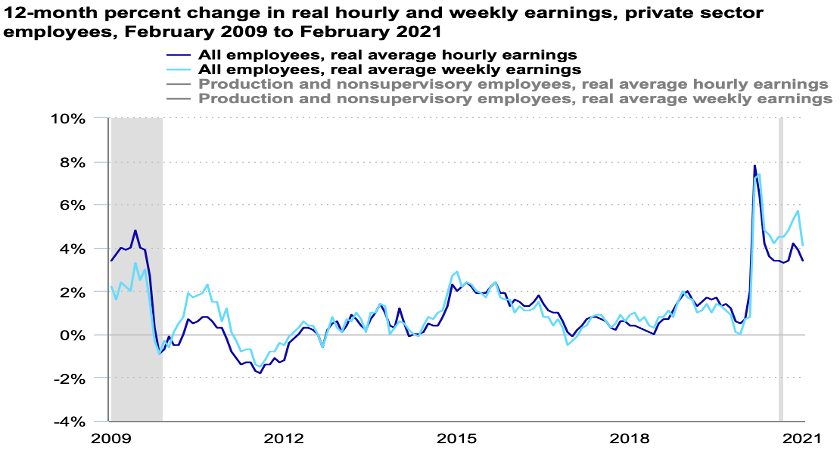

What’s unique about the pandemic is that wage growth accelerated as the unemployment rate shot up.

Over a nearly twenty-five-year period through 2020, average hourly earnings (AHE) growth typically varied between 2 and 4 percent. Looking at the two prior recessions, AHE growth slowed with the onset of each downturn and stayed at a lower level for several years after the end of the recession. By comparison, AHE growth increased an unprecedented 3 percentage points at the peak of the pandemic.

There’s a good reason for this. Low-wage workers disproportionately lost jobs in the recession. The Dallas Fed calculates the mean 2019 hourly wage for individuals not working in 2020 was $18.18. In contrast, the mean 2019 wage for individuals still working in 2020 is $23.46. That is, individuals who lost their jobs earned wages that were on average lower by $5.28, or 23 percent. This composition change is what boosted AHE.

An implication is that composition effects will likely make AHE growth appear sluggish this year due to displaced low-wage workers regaining employment as the economy recovers from the pandemic. Wages for all employees grew 3.4 percent in February.

Source: BLS

Productivity Trends

What’s surprisingly missing from the public inflation narrative is the trend of productivity. Labor productivity growth in the US accelerated from just 0.4 percent in 2016 to 1.8 percent in 2019. In 2020, productivity rose 2.5 percent, the fastest pace of growth since 2010.

A new era of productivity-led growth (similar to the early 1950s, 1960s, or late 1990s) would be unbelievably bullish for markets. Investors are paying scant attention to the possibility of such an outcome.

Rising productivity increases living standards, allowing wages and profits to rise simultaneously, and boosts supply to meet rising demand, which helps mitigate cyclical inflation and interest rate pressures.

As an example, if trend productivity growth is 2 percent, this implies that nominal wage growth of 2 percent puts zero upward pressure on overall prices. And nominal wage growth of 3.5 to 4 percent would be consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target. Only wage growth being sustained above 4 percent (unlikely given what we discussed) would lead to inflation overshooting to the upside.

All of this means inflation anxiety is overdone. And we have not even dwelled on the structural forces still at work that are conspiring to restrain inflation pressures, such as aging demographics and digital adoption.

Investment Insights

If inflation remains generally subdued, as we expect, the Fed will keep delaying the start of policy normalization. This is bearish for the dollar and presents a strong backdrop for risk-taking. A taper tantrum is far from inevitable.

Market-based inflation expectations are more strongly influenced by short-term oil-price movements than underlying economic data. The 10-year breakeven inflation rate is up to 2.31 percent from 1.65 percent in November. Oil went from $37 to as high as $66 over the same period. With the Chinese credit impulse rolling over, commodity prices will struggle to sustain their massive rally. The corollary is inflation expectations may be close to peaking.

Last May, we reviewed all the big declines in bond yields since the beginning of the secular downturn in interest rates in 1981. From each historic low, the 10-year Treasury yield retraced 50 to 61.8 percent of the drop. The key insight was that the 10-year yield could reach 1.8 percent in 2021 (the 50 percent retracement of the decline from 3.2 percent in October 2018 to a low of 0.4 percent in March 2020). That seems like a natural level to start leaning into long bond positions given our inflation outlook.

Investors reported the biggest cut in fifteen years to their exposure to technology stocks, which took a hit as yields marched higher. Buy into this weakness. We believe high-quality, secular growth stocks will start outperforming once again.

There are all sorts of stories about inflation. We choose facts over fiction.

Photo: Bloomberg