In a new bull market, you can almost feel the greed tide begin.

Usually it appears a few years after the market bottom, but this time is different. The coronavirus pandemic has made death salient, spurring certain psychological tendencies. Buying stocks is one result.

The cognizance of death, and our innate fear of it, drives much of our conscious and subconscious behavior, according to psychologist Sheldon Solomon. When mortality is front and center, as it is right now, people turn to money for security.

They want to feel safe, and money is a proxy for safety. For some people, “the acquisition of money is a death-denying fetish,” says Solomon.

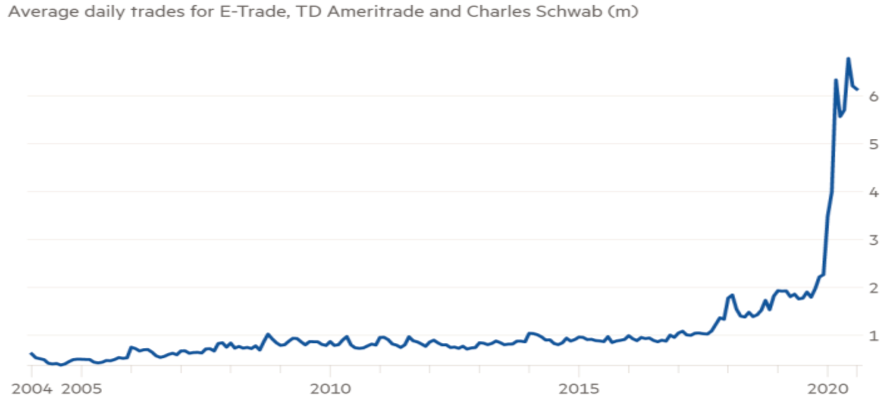

Conspicuous consumption of stocks, bolstered by the frictionless appeal of zero-commission trading, has increased for this reason. Daily trades across the big US retail brokerages ETrade, TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab have more than tripled. Retail traders now make up 20 percent of US equity trades, double last year’s total.

Source: Financial Times

From a psychoanalytic point of view, stocks have become “phantastic objects” in the minds of investors, defined as something which fulfils our deepest desires (in this case for security and protection).

Freud argued the reality of our minds follows two principles, the “pleasure principle” and the “reality principle.” The former makes us seek continual enjoyment and gratification, while the latter appeals to reason and creates resistance to avoid any negative outcomes.

In rising markets, unconscious phantasy takes over from reality‐based thinking. There is no downside to speculation as anxiety and risk are vanquished by the mantra “stocks only go up.” A phantastic object makes one feel good and unconsciously omnipotent.

Not everyone in a market has to be a believer. Indeed, the vast majority are unable to break free from the “reality principle” to assess the generalized belief that something “phantastic” is happening. Those who make rational arguments and remain vigilant tend to lose their credibility. Stars like Dave Portnoy are born.

The active behavior of the believing group is sufficient to move prices. The pleasure principle creates its own momentum. When enough people pursue phantastic objects in a contagious new reality, excitement can become self‐fulfilling. Investors believe it is much less risky to invest than to miss out on investing.

They buy something they hope will go up 50 percent in three years. But this seems much too slow when there are stocks around that are going up 100 percent in three months. “The greed itch begins when you see stocks move that you don’t own,” writes George Goodman in The Money Game. “Then friends of yours have a stock that has doubled. Or, if you have one that has doubled, they have one that has tripled.”

It has been said before: there’s nothing as disturbing to one’s wellbeing and judgment as to see a friend get rich. Time horizons, risk appetite and money goals change. Eventually, it all turns into a marvelous mania that is great fun as long as you know when to leave the party.

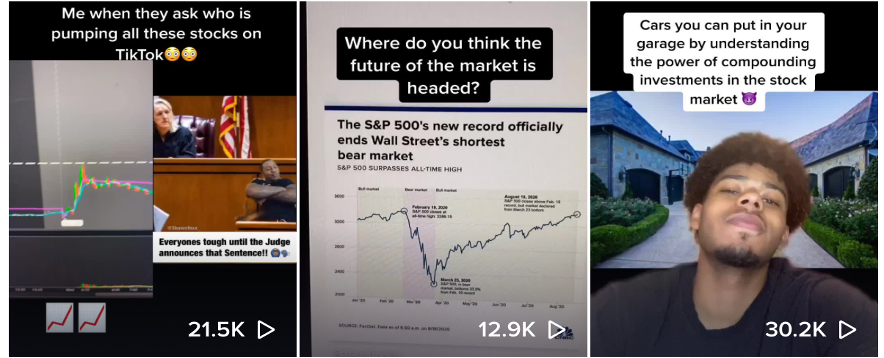

We believe it is much too soon. Young HENRY—“high earner, not rich yet”—has only just arrived at the scene.

Source: TikTok

Feeding the greed tide are looser regulations and the popularity of new investment vehicles.

On August 26, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) changed its definition of “accredited investor” to remove the requirement that managers of certain high-risk funds can only accept capital from investors with assets of $1 million or more. Individuals will now be able to qualify as accredited investors based on their professional knowledge, experience or certifications.

“Why shouldn’t mom-and-pop retail investors be allowed to invest in private offerings?” SEC Commissioner Hester M. Peirce said. “Why should I, as a regulator, decide what other Americans do with their money? The alleged justification is investor protection, but where does that principle take us? Someone who does not invest at all will not lose any money on investments. She will, however, lose. She will lose the opportunity to see her money grow more than it could sitting in a bank account. She will lose the opportunity to be part of enterprises that she believes will transform society. And she will lose her right to make decisions for herself.”

The “accredited investor” definition was first established in 1982. The change represents a major mindset and regulatory shift. More and more people will join the money game.

AngelList has pioneered rolling funds as a way for anyone to launch their own VC fund. These new funds are organized as quarterly subscriptions and allow any accredited investor to buy in for a few thousand bucks. About seventy of these publicly marketable, SaaS-like structures for venture funds have already launched.

Founders and operators such as Gumroad’s Sahil Lavingia are leading the way, but the potential exists for anyone to launch a VC fund as a side hustle. Those with a large Twitter following are jumping on the bandwagon.

Meanwhile, the big names are launching SPACs, blank-check companies formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies, including Bill Ackman, Reid Hoffman, Kevin Hartz, Eric Schmidt, Paul Ryan, Billy Beane, Martin Luther King III, and Shaquille O’Neal. The greed itch has even forced Masa Son to get in the game.

Though SPACs have been around for decades, Chamath Palihapitiya kicked off the frenzy in October last year when his first $600 million SPAC took a 49 percent stake in Virgin Galactic. His second SPAC bought Opendoor last month and his third SPAC plans to merge with Clover Health.

Palihapitiya has raised $2.1 billion across three additional SPACs and reportedly reserved all 26 letters of the alphabet—from IPOA to IPOZ—as public company tickers for SPAC public offerings.

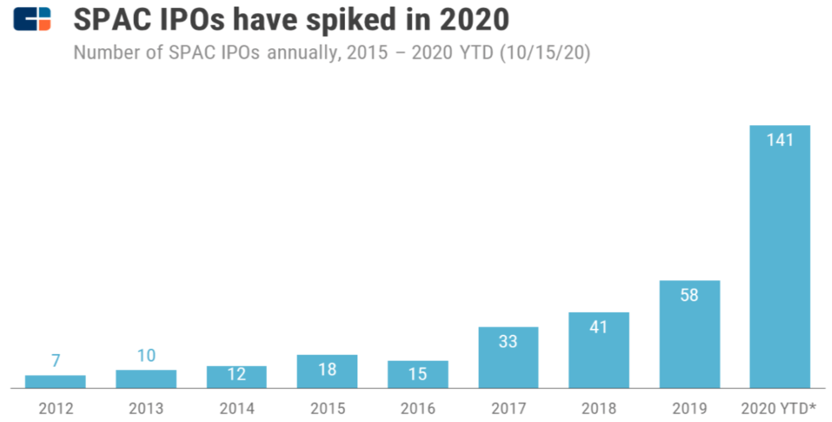

The number of SPAC IPOs has more than doubled in 2020, and SPAC proceeds have tripled the previous record set in 2019. SPACs have raised more than $41 billion, more than the last ten years combined. The average SPAC IPO raised more than $400 million. Another 123 blank-check companies have filed an S-1 but have not yet IPO’d.

Source: CB Insights

“Just as we saw in the ’70s and ’80s, venture capital starts to grow and in the ’90s really takes off, we see the same with SPACs,” notes Kevin Hartz. “This is just the top of the first inning.” We tend to agree. The IPOX SPAC Index, which tracks the performance of the top publicly traded SPACs, only went live on July 31.

There are approximately two hundred public US technology companies with a market valuation in excess of $1 billion. There are another two hundred unicorns that are still private. Benchmark general partner Bill Gurley has come out endorsing SPACs as “a truly legitimate and preferable doorway into the public markets.”

SPACs will basically look to take these private companies and flip them onto the public markets where investors are pouring money into exciting growth stories. We are seeing an IPO boom in the midst of a recession.

Ultimately, this is part of a broader trend. The boom in day trading, the birth of rolling funds, and the rise of blank-check companies all point to one thing: the greed tide is beginning.

Source: News Break