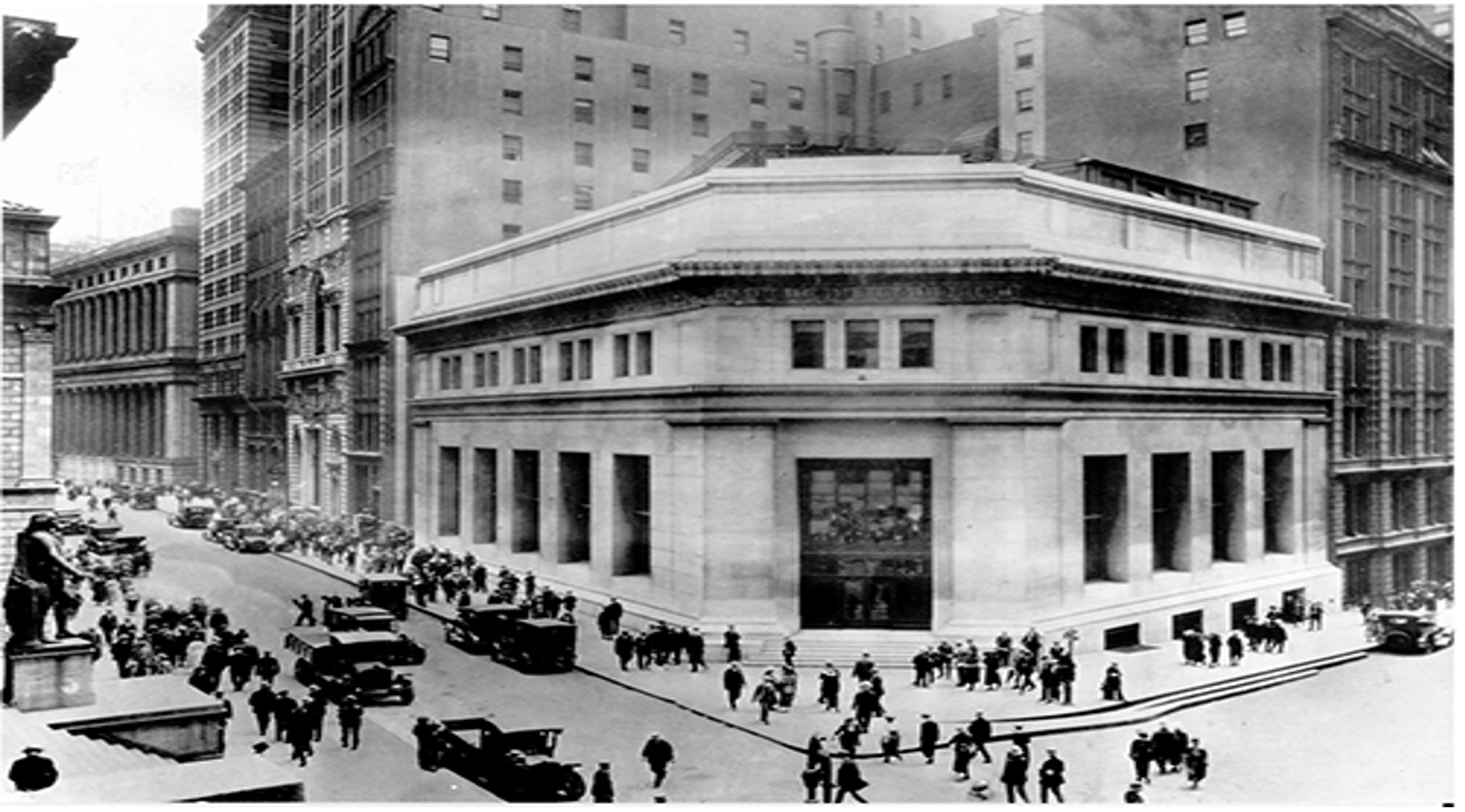

On the southeast corner of Wall Street and Broad Street lay the symbolic and geographical center of American capitalism: the headquarters of J. P. Morgan & Company. From its address at 23 Wall Street fomented the highest aspirations of commercial success and the basest impulses of greed and deception.

It was here that J. Pieremont Morgan stood astride the financial world like a colossus. “Every time [Morgan] saved the market, you could hear the cheers from the exchange floor from across the street at 23 Wall,” the historian Charles Geisst reported. During the panic of 1907, Morgan had bailed out the banks and almost single-handedly saved the market from ruin.

It was in Morgan’s office at 23 Wall that nearly the entire railroad industry was monopolized. It was here that Morgan and Charles Schwab created America’s first billion-dollar corporation, U.S. Steel. The rise of General Electric, General Motors, AT&T, DuPont, IT&T and Con Edison were all engineered in the hallways of this building.

Source: J.P. Morgan Chase

But Wall Street’s centrality to all forms of power and pursuit did not go unchallenged. Here is John Brooks’s description of the events that transpired. We can get the feel of the social context.

In the nineteen twenties, Wall Street ... was a kind of super-university as well as a marketplace. The young Corinthian of ambition, coming there in those days to learn the bond business, could get an Athenian education in manners as well as a Spartan outlook as to life strategies while meeting the people who would help him to become first rich and later influential.

Walking the storied canyons, as compact as a large campus, as ingrown as any academic community, he might brush shoulders with the newly mighty or the ancient great. Then having profited over a period of fifteen or twenty years, he would find the grandees he had met along the way easing his path into the important clubs, committees, and even councils of state.

Wall Street triumphed over (or perhaps profited by) its limitations of space, function, and human situation and emerged as a kind of American Mount Olympus where the gods walked, bluffed and blustered, gossiped, made mistakes, and sometimes touched aspiring mortals with financial godhood.

Brooks goes on to describe the changing of the guard, both in terms of the makeup of Wall Street’s denizens and the relocation of the power centers as corporations moved uptown. “Wall Street took to living with its hat on,” he writes, “ever ready to jump in a cab and fight traffic through the tortuous streets to midtown where the big clients held court.”

Source: 6sqft

The center of capitalist gravity swung back downtown as the Chase Manhattan Plaza finished construction in 1961. By this time, Brooks explains, what was valued in a financier of note was in flux: Old World manners meant less, and a knack for securing returns meant more (“performance” was a new key word in Wall Street).

The new downtown religion was liberal Judaism. German Jews had been among the founding fathers of Wall Street; the Seligmans, the Lehmans, the Goldmans and the Sachs had founded American investment banking before even Pierpont Morgan’s bulky presence had arrived on the scene. The Jews of Wall Street had enjoyed recognition ... but they were by common consent excluded from the formal and official Wall Street leadership.

Brooks engagingly describes how the new movers and shakers of Jewish descent in the 1960s, many of them from Eastern Europe, were more comfortable with notions of stature and leadership than the successful cohorts that preceded them.

The new Jewish men of power were not religious any more than the old Protestant ones had been, but they, like the Protestants, brought with them a certain culture and set of attitudes, which became the new climate of Wall Street. It was a style more inclined to dash and daring as opposed to respectability, less concerned about preservation of values and appearances and more sympathetic toward speculation and outright gambling.

There are, essentially, two stories being told here.

The first is that, through history, Wall Street has been a microcosm of America. The people and social context change, but the desire to become rich remains constant. “If the certificate and the floor go,” Brooks mused in 1973, “Wall Street will have moved a long way toward transforming itself into an impersonal national slot machine.”

The second is that the exodus from Wall Street has been proceeding, gradually, for fifty years. But it took a pandemic to empty out New York’s financial district.

Source: Shutterstock

An irritated Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan Chase, is fretting openly about the need for their employees to return to the office. “We want people back to work, and my view is that sometime in September, October, it will look just like it did before.” But Dimon is ignoring how the pandemic has prompted people to fundamentally rethink their working life. The reign of the investment banker as society’s leading figure of wealth and influence is over.

Once again, Wall Street seems poised on the verge of a take-off into new, totally unexpected, and totally uncharted directions.

Untethered to the physical world, the largely pseudonymous crypto community is unifying many thousands. They share a disdain for fiat currencies, untokenized assets, opacity, and the built-in inefficiencies of money and finance. Theirs is a style more inclined to experimentation. Democratization is the new key word.

Decentralized finance (DeFi) represents a crowdsourced effort to reinvent Wall Street on the blockchain, cutting out middlemen with a permissionless and much more peer-to-peer ecosystem. One generation of innovation here could outstrip a whole lifetime of change as a new cohort of financial innovators—gamers and hackers, and mostly millennials—tests the limits of markets.

As crypto’s Wild West attracts the greatest money-seekers, the bright and ambitious, the young, and even some veteran bankers, Wall Street’s centrality and grip are ebbing. The future is decentralized.

As for 23 Wall Street, that former temple of American capitalism, J.P. Morgan vacated the premises in the early 2000s, after which it never found an enduring new use, serving instead as temporary quarters for movie shoots, seasonal pop-up shops, and upscale parties.

Wall Street, then, in this sense will become what the painter Willem de Kooning called a “no-environment.” At risk are companies with lots of New York office space like Empire State Realty Trust (ESRT), which owns the Empire State Building, and SL Green Realty (SLG), which owns the immense new One Vanderbilt tower next to Grand Central.

A greater risk dwarfs the question of empty Manhattan square footage, and that’s the expansion of our speculative world beyond limits we can presently imagine.

Picture the tokenization of everything—the act of converting real-world and digital assets into coded tokens that can be traded—feeding our predilection for speculation to the point where the nation adopts the belief that speculation is a more worthwhile way to make a living than to work.