There is room for calm amid the uncertainty about labor shortages and wage inflation, and to understand why we can cast our minds back to the winter before the Great War.

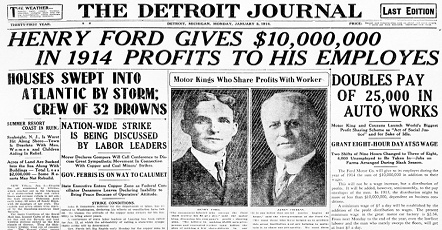

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford made an announcement that shocked the country. At a time when every other manufacturer was trying to cut costs, Ford doubled the pay of his workers at Ford Motor Company and reduced the workday from nine hours to eight hours.

The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board was livid: “To double the minimum wage ... is to apply Biblical or spiritual principles where they do not belong.” The Journal warned that Ford had committed “blunders, if not crimes” that may return to plague the industry and society.

While boosts to productivity cut the time it took to produce a Model T car from 12 hours to 93 minutes, it took a toll on worker satisfaction as skilled craftwork was reduced to repetitive labor. The mundane assembly process bored those who had taken joy in their work. Lateness and absenteeism became a habit for some. Many simply quit.

Ford sought a way to reduce workforce turnover, which plagued the company’s fortunes. His revolutionary announcement amounted to the first time in modern history that employees were viewed as an investment rather than an expense to be minimized.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, profits doubled two years later. It was one of the greatest business decisions of all time. As Ford put it, the “five-dollar-day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made.”

Source: The Detroit Journal

Many large corporations raised pay in the 1920s, launched pensions, and started offering healthcare benefits, acting out of a mix of paternalism and self-interest. The government also played a role. In the 1930s, legislation handed unions more influence and established a federal minimum wage.

While all of this led to improvements in living standards, the corporate world wasn’t happy with labor’s ascendancy.

Top corporations like General Motors and Goodyear challenged these reforms and prepared for violent confrontations with labor organizers by stockpiling guns and dynamite. They infiltrated union groups with their spies, and they formed squads to attack pro-union activists. These schemes, revealed in Senate hearings in 1937, put corporations on the defensive.

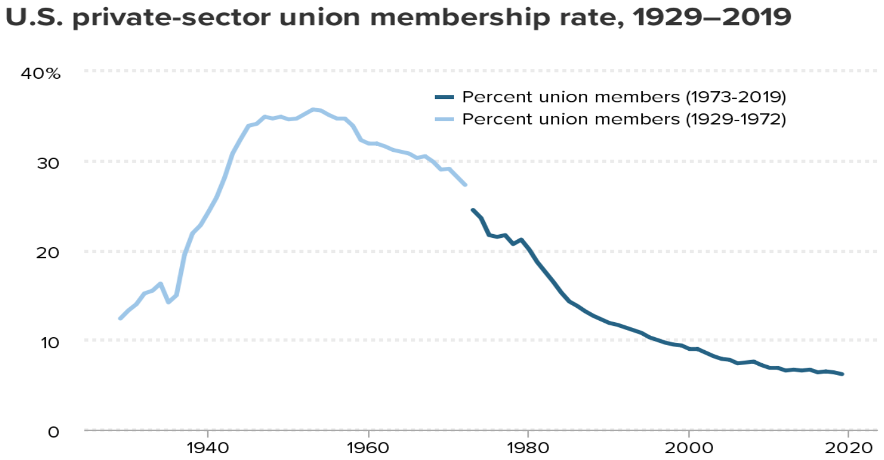

During the quick defense build-up for World War II, tight labor markets allowed unions to gain more power. By 1945, one out of every three non-farm workers belonged to a labor union—an apex.

Source: Street Roots

According to Lane Windham’s book Knocking on Labor’s Door, organizing a union was “the narrow door” through which working people accessed social welfare benefits such as health care and retirement.

If you are German or French, you don’t have to join a union to have access to healthcare or retirement. Those are benefits provided as a matter of citizenship. In America, employers provide those benefits to workers. How do we ensure that corporations step up to play this role? Through firm-level collective bargaining. So unions play a critical role in our social welfare system—they do the redistribution work that governments do in many other countries.

In the 1946 election, the Republicans gained control of Congress after eighteen years. Of the 318 candidates endorsed by the various political action committees under the aegis of organized labor, only 75 were elected. Numerous anti-union rulings followed. During the Eisenhower years (1953-61), corporations made even more progress in watering down regulatory protections.

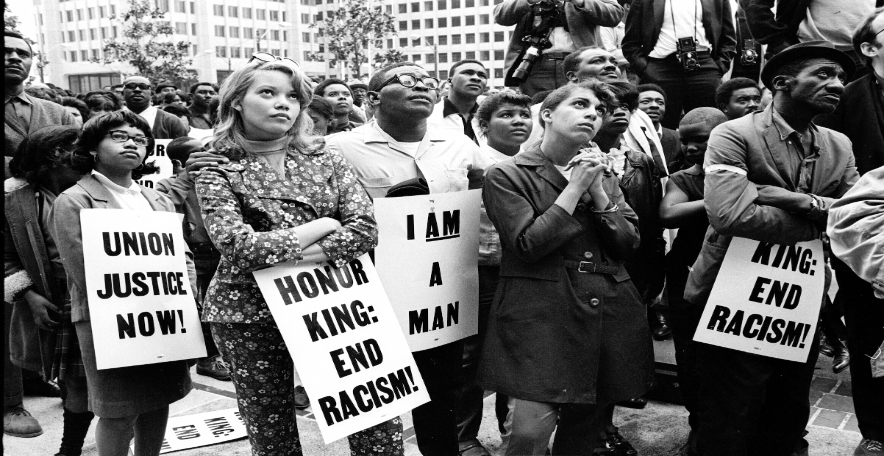

Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a great many women and people of color joined unions, and this posed a huge challenge. The United Auto Workers, the most progressive industrial union, was unable to maintain a cross-class, multiracial coalition committed to continued labor reform. It lost the support of its major allies and the trust of many of its white members.

Source: Time

The period’s mild inflation was diagnosed as “cost-push” inflation by conservative economists. All talk of price-fixing by corporations and rising raw material prices was brushed aside, and the power of organized labor to extract annual cost-of-living adjustments was alleged to be the main culprit. A new consensus emerged that government was at fault for aiding unions.

One out of every six union members went on strike in 1970. This includes the greatest wildcat strike in US history: 150,000 postal workers put down their mailbags and picketed—illegally. Corporate opposition to unions grew stronger in the seventies as manufacturers struggled against global competition.

Then came a string of setbacks, including recession, inflation, and the oil crisis. Businesses responded by dismantling the entire employment relationship. They cut labor costs, sidestepped their social welfare obligations with part-time workers and subcontractors, and entered the political fray more aggressively.

Since launching their offensive in the seventies, corporates never took their foot off the gas. This sustained effort is at the heart of the dramatic increase in income inequality. In his book Staying Alive, Jefferson Cowie dubs that decade as “the last days of the working class.”

Source: Economic Policy Institute

With high unemployment, the shift to offshore production, and the decimation of unions by corporate attacks, President Reagan delivered the final blow by overturning many pro-labor policies made by the Democratic majority during the Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter administrations.

Management styles gaining traction in the eighties advocated reduced pay for low-wage workers, the further dismantling of unions, and contracting out work to cheaper venues abroad. Labor was not viewed as an asset but as a cost on the balance sheet that needed to be managed. Outsourcing was rationalized as merely good business.

As time went on, companies forgot how to compensate workers fairly and workers forgot what they deserved. Both were deeply scarred by the Great Recession. Firms neglected to raise pay as a matter of course, while employees hesitated to ask for fairer compensation or leave for a better opportunity.

In January 2012, Caterpillar locked out union members at a locomotive factory in Ontario when they rejected a nearly 50 percent pay cut; the unit was shut down, and production was moved to Indiana, where workers accepted lower wages. At another Caterpillar factory, employees caved after three months of resisting cuts to healthcare and other benefits.

“I always try to communicate to our people that we can never make enough money,” Caterpillar CEO Doug Oberhelman said. “We can never make enough profit.” He bullied unions to accept a six-year wage freeze in 2013. Meanwhile, employees at McDonald’s and Walmart were so underpaid they still qualified for government assistance.

The assault on wages, benefits, and the dignity of a good job continued with the rise of the gig economy. New legal constructs denied gig workers the right to worker protections that people fought to win a century ago. Uber and Lyft, in securing the passage of Proposition 22 in California, allowed on-demand companies to continue treating their drivers as independent contractors rather than employees.

Source: Protocol

In The Great Demographic Reversal, economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan contend that the balance of power between labor and capital is all about supply and demand. The full entry of baby boomers into the workforce, including an increasing number of women, along with the rise of China and other emerging economies, resulted in the largest positive labor supply shock in history. They argue that a weakening of labor relative to capital was unavoidable.

Large American corporations in the eighties sent less than half their earnings to shareholders, spending the rest on their employees and other priorities. But between 2007 and 2016, they dedicated 93 percent of their earnings to shareholders, a very narrow class of people.

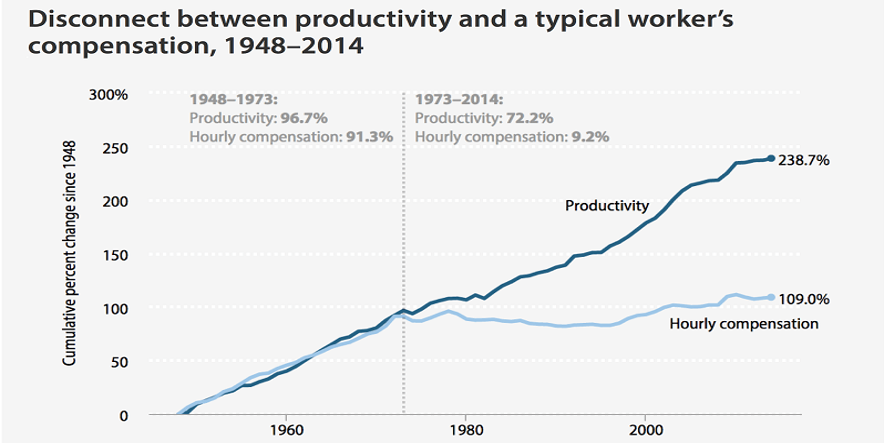

In recent decades, US productivity gains have increasingly gone to capital rather than labor. Between 1973 and 2014, net productivity grew by 72.2 percent, but typical workers’ pay rose just 9.2 percent, or only one-seventh as much.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

Adam Smith made it abundantly clear in The Wealth of Nations that the wages of “the laboring poor” are the true measure of a nation’s wealth; high profitability and wealth concentration was a sign of economic disease. “The rate of profit,” he argued, “is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

Though Henry Ford pioneered a new way of thinking about the relationship between employers and employees, corporations used every strategy conceivable to keep employees in check and grow profits. This is still the case. But there is hope labor and its interests may start to get the attention they deserve.

The pandemic has stoked what economists are dubbing “the great resignation.” American workers are quitting at the highest rate in decades. We’ve never seen anything quite like it. Surveys show anywhere from 25 percent to upwards of 40 percent of workers are thinking about leaving their jobs in search of more pay, more flexibility, or more happiness.

According to a CNBC Global CFO Council poll, US-based companies are increasingly finding it difficult to hire, and more than 90 percent of them are raising wages, in turn contributing to worries over inflation. Despite anecdotal tales of woe, however, wage increases thus far are concentrated in low-wage service jobs.

As the number of unfilled jobs continues to grow, some believe the 2020s could be the decade when workers reclaim the reins of power. The data, on the other hand, contradicts this.

Since the end of the recession in April 2020, the median hourly wage for employed workers has actually fallen to around $22 as the unemployment rate dropped and lower-wage job numbers went up. It’s feasible to think it’ll fall even lower as the number of people holding lower-wage jobs returns to pre-pandemic levels.

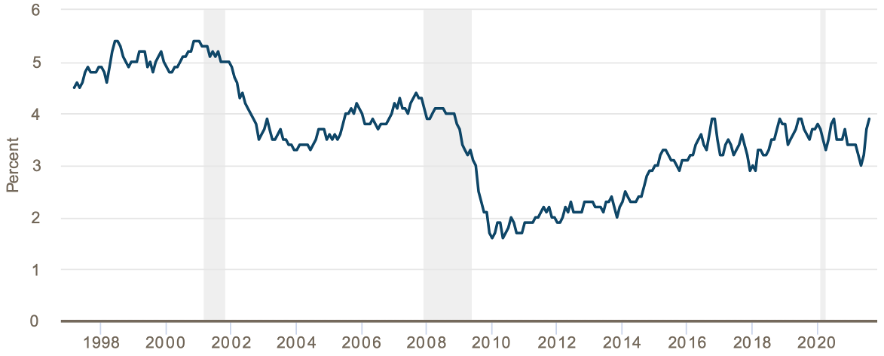

The Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker shows wages rising at a 3.9 percent pace, which is fairly consistent with the past few years and still below levels preceding the Great Recession.

Source: Atlanta Fed

It is hard for us to fully share the optimism that we are on the cusp of redressing the current power imbalance in the labor market. Today’s perceived labor shortage—the coexistence of record job openings with high unemployment—reflects labor market re-equilibration during a period of rapidly rebounding demand.

We are, in fact, living in a period of technological deployment. Technologies that reduce labor utilization and augment productivity will help companies operate amid labor scarcity. A global survey of chief information officers by Gartner found that more than 90 percent plan to have deployed AI technology in some form within the next three years.

In the end, wage inflation isn’t something we’re concerned about. The pursuit of profits lives on.

And now, some poignant words from Louis L’Amour, taken from his book Bendigo Shafter.

My friend, there is a Hell. It’s when a man has a family to support, has his health and is ready to work, and there is no work to do. When he stands with empty hands and sees his children going hungry, his wife without the things to do with. I hope you never have to try it.