A narrator in Dashiel Hammett’s novel The Dain Curse attempts to persuade a woman that she is absolutely fine, while she believes she is under a curse:

Nobody thinks clearly, no matter what they pretend. Thinking’s a dizzy business, a matter of catching as many of those foggy glimpses as you can and fitting them together the best you can. That’s why people hang on so tight to their beliefs and opinions; because, compared to the haphazard way in which they arrived at, even the goofiest opinion seems wonderfully clear, sane, and self-evident. And if you let it get away from you, then you’ve got to dive back into that foggy muddle to wangle yourself out another to take its place.

Even the most intelligent people can become lost in a fog. Those who appear certain of themselves are trying to suppress their inner doubts. When it comes to Fed policy and inflation’s grip on the economy, we’d all be better off if we just admitted how confused we are.

We’re perplexed by Fed vice chair Richard Clarida’s remarks that lowering the unemployment rate to 3.8 percent next year, from 4.6 percent now, would be compatible with his assessment of maximum employment and warrant tighter monetary policy. Nine of the eighteen Fed officials are penciling in a 2022 liftoff.

In 1950, the Review of Economics and Statistics held a symposium titled “How Much Unemployment?” which debated the accuracy of the Census Bureau’s value for unemployment. Wharton professor Gladys Palmer, a renowned labor expert, argued that “a single figure of unemployment, regardless of how it is defined or derived, is inadequate” to guide monetary policy decisions. She claimed that no single number could fully sum up diverse labor force activity.

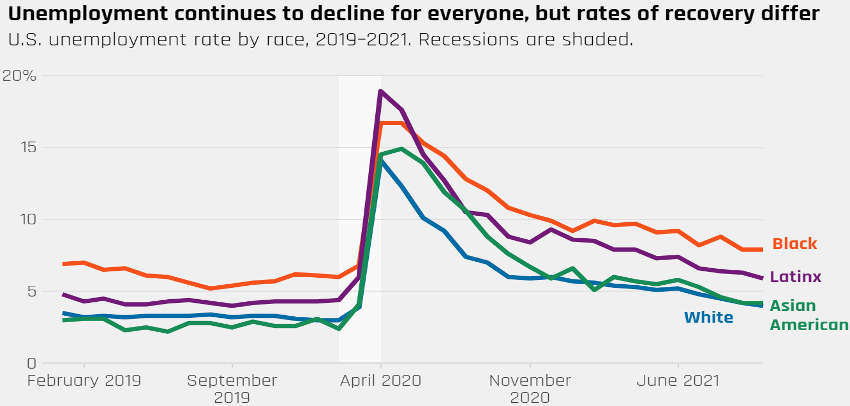

If we look beneath the headline unemployment rate, the jobless rate varies for adult women (4.4 percent), teenagers (11.9 percent), whites (4.0 percent), and blacks (7.9 percent). The present unemployment situation for black Americans is what white Americans experience during a recession. (The gap between the black and white unemployment rates is 3.9 percentage points. The narrowest it reached was 2 percent in August 2019.) The unemployment rate for those without college degrees is 5.4 percent, up from 3.5 percent in February 2020.

Source: Equitable Growth

“It’s appropriate to be patient,” Fed chief Powell said, noting the considerable ground that still needs to be made up to repair the labor market. The Fed’s new monetary policy framework has redefined the full employment mandate to a broad and inclusive goal.

The number of unemployed persons stands at 7.4 million. Assuming payrolls growth averages 500,000 per month going forward, it would take more than a year to “eliminate shortfalls from maximum employment.” Thus far, monthly job growth has averaged 582,000 in 2021.

Our assertion is that the pandemic has caused lasting damage to labor supply. But we realize that a similar debate played out following the Great Recession and the participation rate for individuals in their prime working years fully recovered from its post-crisis decline (something we predicted at the time).

Between 2015 and 2019, 3.5 million prime-age Americans joined the labor force, nearly 1 million people moved out of long-term unemployment, and 2 million involuntary part-time workers secured full-time jobs. Here’s what Powell learned from the Fed’s first-ever public review of its monetary policy framework:

As we heard repeatedly in our Fed Listens events, the robust job market was delivering life-changing gains for many individuals, families, and communities, particularly at the lower end of the income spectrum. Many who had been left behind for too long were finding jobs, benefiting their families and communities, and increasing the productive capacity of our economy.

Before the pandemic, there was every reason to expect that these gains would continue. It is hard to overstate the benefits of sustaining a strong labor market, a key national goal that will require a range of policies in addition to supportive monetary policy.

Source: Federal Reserve

It’s worth remembering that the Fed took seven years to lift the fed funds rate from zero in the previous cycle, a move that was deemed premature and forced the Yellen-led Fed to pause for another year. Fed officials admitted the 2015—18 interest rate hikes were a mistake in retrospect. Marginalized people such as low-income and black workers are among the last to experience employment gains in an economic recovery. “The gains would have been greater,” Fed governor Lael Brainard said, had they waited.

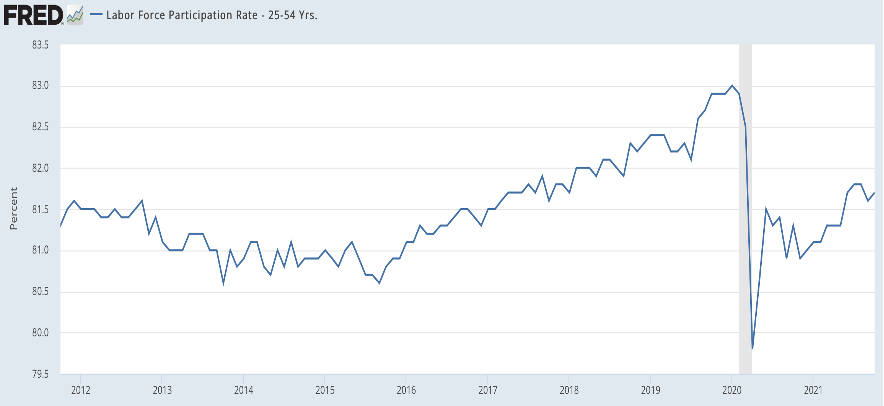

The corollary is that the Fed will want to see improved outcomes for people on the “margins” of the economy, so it may keep waiting for the prime-age labor force participation rate to return to pre-pandemic levels to assess the employment picture. It sits at 81.7 percent today and was at 83 percent in February 2020.

“There’s room for a whole lot of humility here as we try to think about what maximum employment would be,” Powell said recently. The last economic cycle, he said, showed that “over time you can get to places that didn’t look possible.”

Brainard, a significant contributor to the revamped policy framework that the Fed unveiled in August 2020, said “I see no reason the labor market should not be as strong or stronger than it was pre-pandemic.”

Once again, the Fed’s humanitarian mission, to get back to a strong labor market that benefits all Americans, rather than act on inflation fears, has come to dominate economic policymaking.

Source: St. Louis Fed

It also helps that when tapering concludes in the middle of next year, year-over-year inflation readings will be cooling off.

Base effects will undoubtedly fade, and inflation will return to trend levels as the spike in a small range of prices (notably for autos, airfares, and hotels) subsides. We expect core PCE inflation to peak at over 4 percent in the first quarter, then fall to around 3 percent by the summer before ending up just above 2 percent by the end of 2022. The Fed will be relieved of the burden that consumer prices are spiraling out of control in the face of declining inflation.

A concern is that the cost of housing services, or shelter, could become one of the more persistent factors in higher inflation.

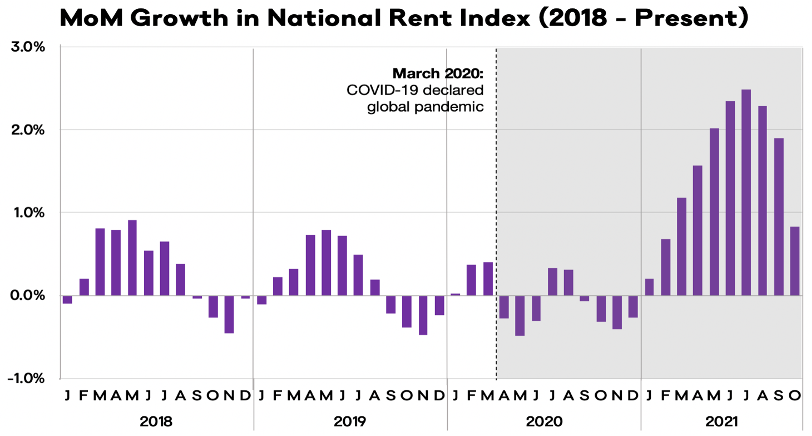

The national median rent has increased by 16.4 percent this year, according to data compiled by Apartment List. To put that in context, rent growth from January to October averaged just 3.2 percent in the pre-pandemic years from 2017 to 2019. But there are signs the rent market is starting to cool.

Rents grew by 0.8 percent last month nationally, the third straight month that growth has slowed, after peaking at 2.6 percent in July. According to Apartment List’s national index, 22 of America’s 100 largest cities saw rents fall last month, ending a six-month stretch in which virtually all these cities were experiencing uninterrupted rent growth.

Source: Apartment List

After bottoming at 3.8 percent in August, Apartment List’s vacancy index has also ticked up for two straight months and now stands at 4.1 percent, signaling that tightness in the rental market is beginning to ease. The end of the eviction moratoriums will boost the vacancy rate further and may in fact constrain the unprecedented rent growth that has characterized most of this year.

A study by the Washington State Women’s Commission found that only 15 percent of evicted renters move to another permanent home; 37.5 percent end up being homeless; 25 percent move into shelter or transitional housing; 25 percent move in with family or friends; and 80 percent report being denied new housing due to their past evictions. There are least 2.5 million households significantly behind on rent and at risk of eviction without policy support.

Current house price growth is most strongly correlated with owners’ equivalent rent inflation sixteen months later. Higher rents take time to appear in inflation data because leases tend to last a year and the Bureau of Labor Statistics samples rents only every six months.

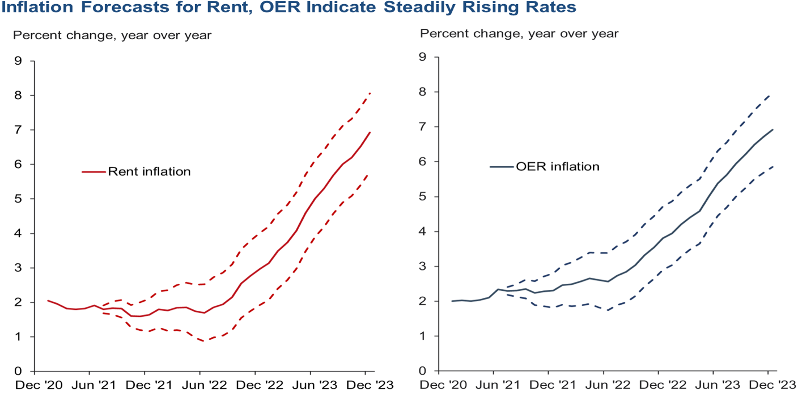

Prior to the pandemic, shelter inflation, which accounts for 17 percent of core PCE, was averaging over 3 percent a year. Based on the Dallas Fed’s projections, we won’t get to those levels until year-end 2022. The real upside to shelter comes in 2023, when it is expected to surge to 6.9 percent and add about 1.2 percentage points to core PCE.

Source: Dallas Fed

That leaves us pondering higher wages. The Employment Cost Index increased by 1.3 percent in the third quarter, reaching its highest level since 1991. Year-over-year growth is now 3.7 percent.

With labor productivity averaging 1.6 percent since the pandemic began, the level of wage growth is desirable and consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target. Only if wage growth exceeds 4 percent for an extended period and productivity does not improve as we expect will inflation overshooting be a concern.

As we wrote last month, it is hard for us to fully share the optimism that the 2020s could be the decade when workers reclaim the reins of power.

While the five and ten-year break-even inflation rates are flirting with historic upside ranges, we suspect this reflects changes in inflation risk and liquidity premia more so than a reacceleration in inflation expectations. Survey data has also systemically over-projected actual inflation since the 2000s.

The Fed staff have created what they call the Common Inflation Expectations (CIE) Index, which combines 21 indicators of inflation expectations, including readings from consumer surveys, markets, and economists’ forecasts. The current reading of 2.06 percent, which is firmly within the range that prevailed before 2014, indicates that inflation expectations are well anchored.

The basic conclusion is that, contrary to popular belief, inflation will not be a defining issue for the coming year. Our contrarian Fed view makes us bearish on the dollar.

Most people see the dollar index breaking out of a double bottom pattern. That is the correct near-term interpretation with an upside target of 96. But we also see a complex multi-year diamond top pattern, which confirmed the dollar’s reversal last summer. The countertrend move ought to end no higher than the 97-98 area.

Source: Tradingview.com

Every dollar bull market since 1970 has been marked by an increasing real neutral rate, which has aided in attracting funding from around the world. But with the Fed on hold as inflation stays elevated, real yields are hovering near record lows. (The 10-year real yield has been in negative territory since March 2020). Add in a record trade deficit and bleak budgetary outlook, and the fundamentals appear to be shaky. A hawkish turn in other central banks language and actions puts the dollar rally at risk.

We’re bullish on gold. It is an essential asset to own as a hedge against dollar weakness and a drop in risk assets. In the fourth quarter of 2018, when the S&P 500 tumbled nearly 20 percent, gold rallied 8 percent and gold miners were up 13 percent. After a middling performance this year, we expect gold to breakout to all-time highs in 2022. That’s not a goofy opinion.