It was brutal. Global equity markets had lost more than $4 trillion in value after just ten trading days in 2016. Stocks had never fallen so far or so fast at the start of a year. The S&P 500 was down 11 percent. China was in a bear market. There was growing nervousness about a full-blown financial crisis.

By the third week of January, oil was selling for $27 a barrel, a price last seen in 2004. Crude inventories in the US were at their highest level since 1930. Widening credit spreads—driven by the blowout in energy spreads—led to fears of financial contagion. Investors concluded that the US economy is recession bound.

In China, a hard landing was “practically unavoidable,” according to George Soros. The $800 billion decline in China’s FX reserves was taken as proof that the authorities had lost control of the economic situation. The prevailing wisdom was that China must now devalue its currency to boost growth. Hedge funds declared “war on the renminbi,” predicting a 30 to 50 percent drop.

At the end of January, the Bank of Japan delivered another shock to markets by embracing a negative interest rate policy. The consequences were felt right away. The bank selloff intensified, and roughly a third of the global government bond market was trading at negative yields.

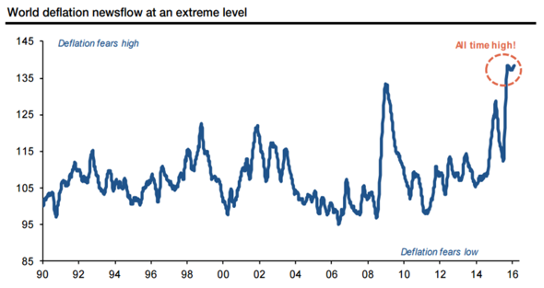

Deflation fears hit an all-time high. “Deflation is the ogre that must be fought decisively,” Christine Lagarde, then-head of the International Monetary Fund, had warned earlier. Nearly 90 percent of the industrialized world economy was anchored by zero rates.

Source: Societe Generale

The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) Sentiment Survey showed that the percentage of bulls among its members was lower than in March 2009 and March 2003, both of which marked the end of bear markets. Our assessment was bullish.

Considering global risk sentiment, we believed that the bullish investment case is not a function of predicting all the good things that can happen. Rather, it was simply establishing confidence that all the bad things that are currently priced into the market will not happen.

That meant betting that (1) the US economy will not enter a recession, (2) China will not devalue its currency overnight, and (3) commodity contagion will not leak into the global financial system. If the major fear factors weighing on global markets fade from memory, the upside in risk assets would take care of itself.

And that’s what happened. Inflation stopped falling, wages were rising, and credit growth had picked up noticeably in the US, Europe, and Japan. There were green shoots of economic improvement around the world, but most investors remained blinded by the oil crash to even notice them.

A procession of good Chinese economic data and fiscal stimulus restored confidence among investors. Despite botched efforts to redesign their currency policy, a yuan devaluation was not inevitable. China didn’t face a major financial reckoning. Economic rebalancing, driven by healthy consumer fundamentals, ensured that growth deceleration is gradual.

Once the shock of the rapid drop in oil prices subsided, price stability helped to reduce credit spreads and volatility globally. Cheaper oil would undoubtedly be an important net positive for the world economy. The negative effect on oil producers initially outweighs the benefits to consumers, but over time, the flow of spending by consumers invigorates growth.

Rather than breaking down from a perilous topping pattern in early February, stocks recovered from the precipice and never looked back. The S&P 500 was up 16 percent in two months and nearly 30 percent one year later.

Source: Tech Charts

The dollar bull market that began in mid-2014 (the largest annual dollar rally in thirty years) was the impetus for the global turmoil. It influenced commodity prices and inflation readings, while global trade declined in value terms (volumes were up, but that didn’t stop the fearmongering about the “end of globalization”). In 2021, global trade reached a record high of $28.5 trillion.

It’s not a coincidence that China’s foreign exchange reserves peaked at $4 trillion in June 2014, just as the dollar took off against other major currencies. The strong dollar also hurt global manufacturing activity (energy and mining account for 40 percent of global capex), and the negative impact was apparent at the corporate level with two consecutive quarters of year over year earnings decline.

Overall, the US dollar, which is a significant macroeconomic factor, warped our perspective of reality. What people failed to realize, however, is that the dollar’s economic and market impact is largely driven by the rate of change, not the level. As the base effects fade, we believed evidence that the economic and earnings outlook is improving would spur greater risk taking.

It’s happening again. But this time it’s the pandemic that has distorted the macro picture. Stocks fell for three weeks in a row to kick off the year. The S&P 500 lost 11 percent, with the tech sector suffering the most. The most pivotal story lines stem from inflation’s relentless march to the highest levels in 40 years and the vexing Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The Fed was communicating that inflation had been transitory, and in December they admitted it’s not. Investors worried that the Fed is pulling the punchbowl and may be forced to tighten monetary policy more aggressively despite slowing economic momentum. Wall Street predicted as many as seven rate hikes this year.

Inflation anxieties have remained since the pandemic, but they intensified after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when oil prices soared to $130 per barrel. The average cost for a gallon of gas in the US hit $4.25 but reached over $5.50 in some places. That’s left some analysts concerned about a potential recession.

Source: Reuters

While we cannot predict the future, we can surely challenge the popular opinion. Our writing duties are a means of determining the consensus as precisely as possible, and then pondering on the opposing alternatives. Because a crowd is susceptible to “contagion,” as Gustave Le Bon phrased it, we examine crowd opinions to avoid the pitfalls of mass unthinking.

Worries about inflation remain entrenched, but the risk is much less prevalent than many think. Base effects will undoubtedly fade, and inflation will return to trend levels as the spike in a small range of prices (notably for autos, airfares, and hotels) subsides. We still believe that inflation will peak in the first quarter and year-over-year comparisons will begin to look less startling.

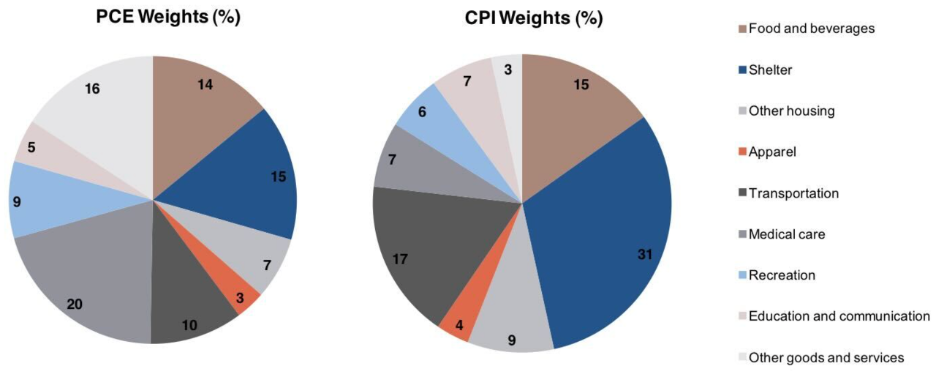

Nearly half of the core PCE index is made up of health and shelter inflation. There is no effect from rising energy costs. Food makes up 14 percent of the core PCE index. That’s mostly beef, pork, poultry, and dairy. Transportation, at 10 percent of the index, is not able enough to influence the inflation trajectory.

The US only buys 1 percent of Russia’s crude production. Spending on gasoline only accounts for about 3.7 percent of consumer expenditures so it’s hardly consequential. Higher oil prices will now be disinflationary, just as lower oil prices were stimulative in 2016. Higher oil prices will also make it financially viable to ramp up production.

Core goods inflation is already slowing, with prices rising 0.4 percent from a month ago, the smallest gain since September. Notably, used car prices declined somewhat from a month ago, a pattern that likely continues based on recent declines in wholesale used car values. Inflation in appliance and furniture prices eased, indicating that supply constraints are less severe. Inflation will plateau as the base effects from the pandemic wear off.

Source: Societe Generale

Taking into account the global risk sentiment, investors need “uncertainty resolution.” They need to see inflation falling. They must be convinced that the economy and financial markets can function at non-zero policy rates. And just as with the pandemic, they need to see markets get desensitized to the Russia-Ukraine conflict. All of this is something we anticipate.

Several key market mysteries will be unraveled in the coming year. The future is not always a reflection of the present. Through the gloom, we see opportunity.