How did we come to believe the Fed has to plunge us into recession to kill inflation? Lowering inflation to 2 percent, posits a recent IMF study, may require a 6.5 percent unemployment rate over a few years. Economist Larry Summers says we need 5 percent unemployment rate for five years.

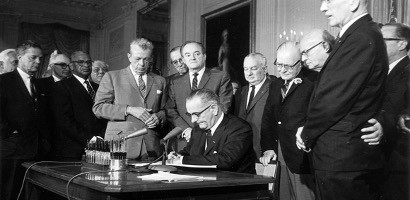

People attempt to understand inflation relative to the Great Inflation between 1965 and 1981, even though today’s macro backdrop is starkly different. Lyndon B. Johnson unleashed a torrent of federal spending after the jobless rate had fallen to 4 percent, which economists at the time considered to be full employment.

“From a macroeconomic policy perspective, it would have been a logical moment to ease up on the accelerator,” writes Ben Bernanke in his book 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19, “but foreign policy and social goals took priority over economic stability.”

Defense spending rose about 44 percent between 1965 and 1968 as America plunged more deeply into the war in Vietnam. President Johnson launched both his war on poverty and the Great Society programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Inflation rose from 1.2 percent in 1964 to 5.9 percent in 1969.

Source: History

The Fed tightened policy in 1969, causing a mild recession in the following year, but inflation never fell below 3 percent. The demise of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 is the next chapter in the story. After the US dollar’s connection to gold was severed, it lost 70 percent of its value, which accelerated the inflationary cycle.

Supply disruptions, notably in food and energy, pushed inflation higher. Oil quadrupled from $3 to $12 a barrel following the five-month-long Arab oil embargo in October 1973. By the time of the Iranian revolution in 1979, oil was nearly $40. This cost-push inflation got passed through the chain of production into higher retail prices.

Motivated by a government-directed mandate to create full employment, the Fed leaned against the headwinds produced by high energy costs and accommodated large and rising fiscal imbalances. Then-Fed chair Arthur Burns later admitted there was a clear sense that addressing the inflation problem head-on would have been too costly to the economy and jobs. Inflation averaged 7.1 percent during the decade, although it hit double-digit levels in both 1974 and 1979.

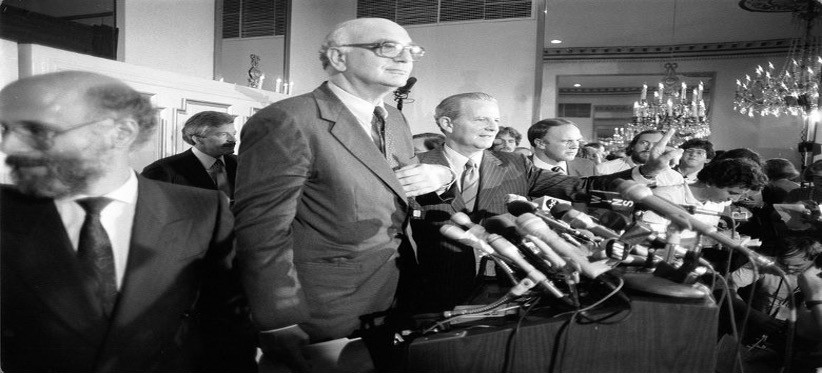

When Paul Volcker became Fed chief in August 1979, fighting inflation was seen as crucial to achieving both objectives of the dual mandate, maximum employment and price stability, even if it disrupted economic activity and briefly caused more joblessness. Volcker’s aggressive interest rate hikes are thought to be what ultimately put an end to the inflationary period, causing the policy rate to rise beyond the neutral rate and to eventually cause a recession.

Source: History

Since then, the Fed’s capacity to directly control inflationary outcomes has received too much approbation. Had the Fed tightened rates dramatically in the 1970s, some claim, the whole problem of runaway inflation could have been avoided. That rate hikes are associated with lower inflation has been accepted knowledge for so long and yet reliable explanations of that interaction are hard to find.

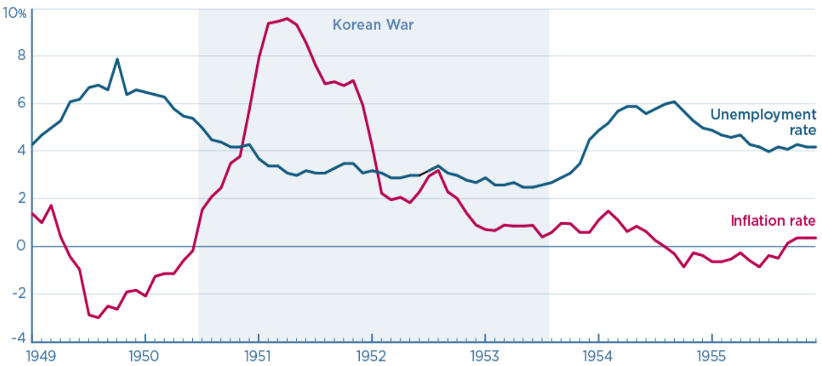

The experience of the Great Inflation inspires the conventional narrative that significantly higher unemployment is required to tame inflation. A historical comparison more appropriate to our understanding could be the surge in inflation in 1951; following the Korean War it was significant but temporary, and it posed no lasting damage to the US economy.

The war started in June 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea and the US economy was recovering from a recession. Then, US unemployment dropped sharply from its peak of 8 percent in October 1949 to just 5.4 percent. Mobilization reduced unemployment to 3 percent by early 1951, a level it remained at until the armistice in mid-1953.

With the tremendous demand driven by the Second World War in mind, producers rushed to build up inventories, speculators drove up the price of commodities, and businesses and workers tried to actively front-run wage and price controls. The result? Inflation rocketed from nearly 2 percent in June 1950 to above 9 percent by early-1951.

Source: San Francisco Chronicle

The Fed had used a form of yield-curve targeting during the Second World War to help the Treasury finance a huge increase in debt. Short-term Treasury bills were pegged at 0.38 percent and longer-term Treasury bonds were capped at 2.5 percent. But soaring inflation alarmed President Truman, and it was decided in March 1951 that the Fed would no longer be required to monetize public debt.

With this newfound independence, the Fed started tightening monetary policy in an effort to directly battle inflation. By 1953, the interest rate on short-term Treasury bills had increased to well over 2 percent. And while such shifts were meaningful at the time, the speed and scale of rate hikes these days make the 1950s interventions pale in comparison. So how did the inflation rate drop to around 2 percent and 1 percent in 1952 and 1953, respectively?

It’s simple. Inflation expectations swiftly normalized as it became evident that the Korean War would not create the same degree of economic restructuring and disruption as the Second World War. The experience of the 1950s shows us that rather than creating a self-sustaining upward spiral, inflation rises and falls as expectations about the future shift. Once the event that drove consumer and corporate behavior to change ceases or capacity adapts, inflation declines.

Source: Peterson Institute

During the pandemic, much of consumer spending moved away from services, like travel, concert attendance, and restaurant dining, and it shifted toward goods, like furniture, electronics, and home improvement products. Retailers scrambled to restock their shelves to meet the demand.

Many chartered their own vessels to bypass the busiest ports and get their goods unloaded sooner. Now, however, they rue their panic ordering and are working to flush out excess inventory—sitting on over $740 billion of inventory as of September as they are, up 22 percent from the same period in 2021.

The cost of shipping freight containers across the Pacific Ocean increased 15-fold during the pandemic. As global supply chain bottlenecks have been repaired, the cost has fallen 88 percent. Spot trucking rates in the US have been declining since they peaked earlier this year, and by the first quarter of 2023 they are forecast to decline by a third.

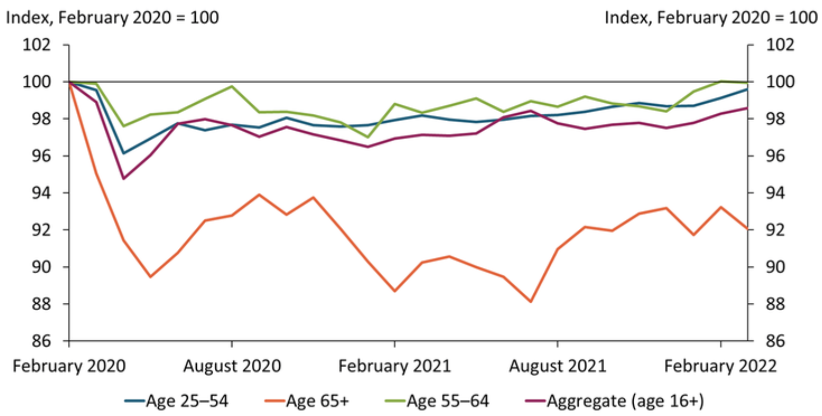

After leaving the labor force in unusual numbers early in the pandemic, an estimated 1.5 million retirees have reentered the US labor market over the past year. Americans ages 55 to 64 are working at roughly their pre-pandemic employment rate. The early-retirement narrative was a myth. Immigration to the US is also rebounding after a sharp two-year slowdown. As the labor market adjusts to post-pandemic realities, wage growth will likely moderate in most sectors.

Labor force participation rates

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Inflationary pressures on goods seem to be easing, and services are next. Inflation in services less rent in October was -0.1 percent month-over-month. And the rate of change for shelter is peaking, with rents for new leases slowing rapidly according to Zillow. If not for the significant price rises in food at 0.6 percent, energy at 1.8 percent and shelter at 0.8 percent, the inflation rate would have fallen by 0.1 percent in October. This is the beginning of a trend.

Inflation is a rate-of-change variable rather than a level. Many people have expressed their displeasure at how costly many products and services have gotten, and they frequently use these high costs as proof that inflation will never fall. This reading, however, is not correct. Prices are unlikely to decrease for most products and services, but if they plateau or increase gradually, their inflation rate will drop to zero or to a small figure.

Our era, like the early 1950s, is characterized by pent-up consumer demand, war-induced uncertainty, and a Fed policy moving from offsetting a national crisis to fighting inflation. Within the next year, we anticipate that inflation will return to levels that will be acceptable to policymakers and will do so without significant job losses.