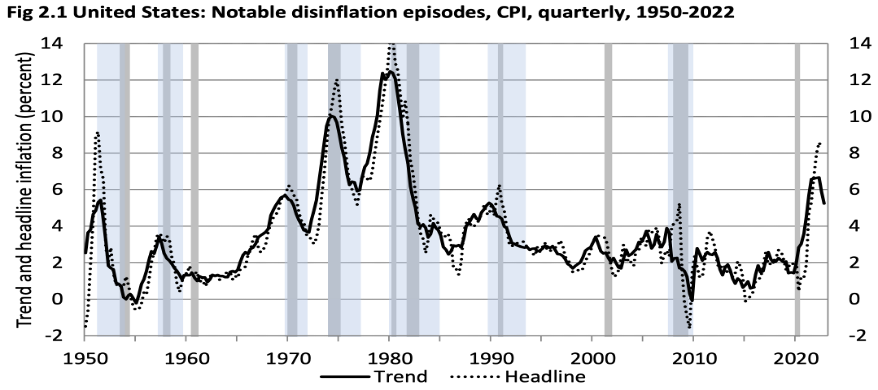

Can the Fed restrain inflation without triggering a recession? A few Wall Street economists doubt as much and published a paper to say so. After examining disinflationary episodes going back more than seventy years, their findings suggest that an “immaculate disinflation” would be unprecedented.

“We find no instance in which a central-bank-induced disinflation occurred without a recession,” the authors write. “The Fed will need to tighten policy substantially more to achieve its inflation objective by the end of 2025.” They contend that raising the Fed’s inflation target is a foolish substitute for making the sacrifices necessary to hit the 2 percent target.

Almost every economist concurs: the Fed’s inflation-fighting exercise will end badly. We are reminded of Humphrey Neill’s potent advice: “When everybody thinks alike, everyone is likely to be wrong.” How can we avoid the pitfalls of mass unthinking?

It is more valuable to consider why we aren’t currently in a recession rather than nervously dreading one. As we often say, our job is not to predict the future; it’s to see the present clearly.

If we can be forgiven, what we observe is so obvious that it surprises us that most others don’t grasp it. Contrary to what many economists believe, the US economy is no longer as sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Source: Managing Disinflations (Chicago Booth)

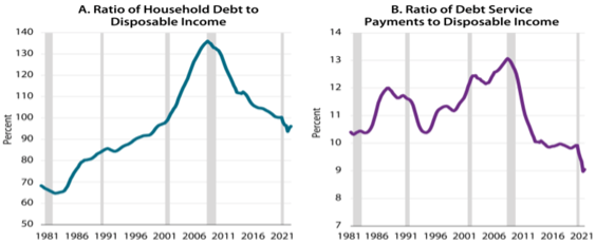

The bursting of the US housing bubble between 2007 and 2009 inflicted enormous damage on household finances. As homeowners’ net worth tanked, many borrowers who had gorged on credit during the boom found the plunge left them highly leveraged.

Total household debt in the US, including mortgages, auto loans, credit card and student debt was $12.6 trillion on the eve of the Great Recession. This debt overhang created a need for household deleveraging which slowed down consumption and the overall recovery. By 2013, American households had lowered their debt burdens by $1.53 trillion, a 12 percent decline.

A decade later, total household debt has reached a record $16.9 trillion. You wouldn’t be amiss to wonder, “What deleveraging?” However, household balance sheets are in much better shape. Revolving credit now accounts for 25 percent of all consumer credit outstanding, down from 36 percent in 2007.

Households used the government’s pandemic aid in part to reduce debt and boost savings, reducing their dependency on consumer credit for spending and improving their loan repayment rates.

Only 11 percent of households used the first government payment to “mostly pay down debt” in 2020, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, but that percentage rose to roughly 50 percent for the second and third payments received in early 2021. Consumers still have $1.2 trillion of “excess cash” in their checking accounts.

The boost to incomes and the fall in interest rates resulted in unprecedented declines in the household debt-to-income ratio, which is at its lowest level since the mid-1990s. And the cost of servicing debt relative to income is at its lowest point since at least 1980 when the data series began. The US household debt-to-GDP ratio is 75.6 percent today compared to 96.5 percent in 2008.

Source: Brookings

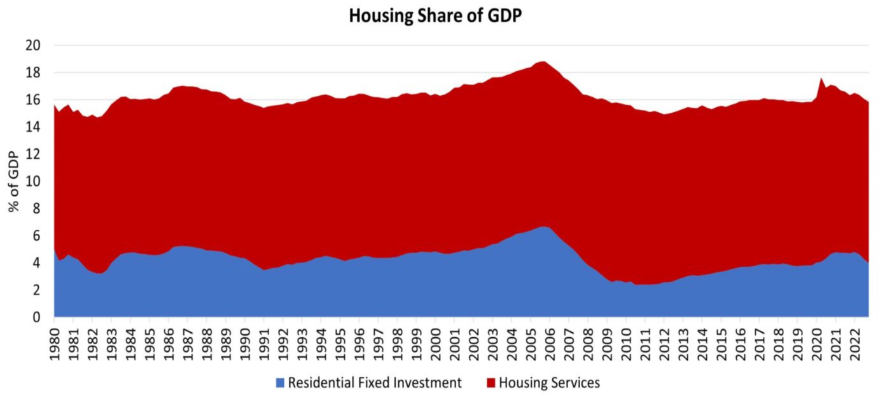

Consider mortgages, which make up the largest component of household debt.

While total mortgage debt at $11.9 trillion is now more than double the 2006 peak, it represents around 40 percent of current home values, the lowest on record. Just 2.5 percent of borrowers have less than 10 percent equity in their homes. There is hardly any negative equity compared to 25 percent of borrowers being underwater in 2011.

There are 2.5 million adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), which make up around 10 percent of the mortgage market. Mortgage debt is now about 65 percent of personal disposable income, versus 100 percent in 2007, and mortgage delinquencies are at a record low, with just under 3 percent of mortgages past due.

Despite concerns about home affordability, there was still $498 billion in newly originated mortgage debt in the fourth quarter. After two years of historically high mortgage origination volumes, the latest figure more closely reflects the pre-pandemic days. Is that really concerning? Or is the housing market just normalizing?

Historically low rates in 2020 and 2021 helped annual home sales soar to levels unseen in more than a decade. Rising mortgage rates have softened demand, but it’s not enough to make a significant dent given many of the conditions that spurred the housing boom are still present—an extreme shortage of for-sale listings, soaring demand from millennials, and better household finances.

Even a small decline in the mortgage rate is enticing more buyers. Sales of new single-family homes increased for the third straight month to a six-month high in February.

Contrary to reports of a “housing recession,” residential fixed investment still represented 4.4 percent of GDP in 2022 as opposed to 4.8 percent in 2021, and housing services’ share of GDP was 11.8 percent, down from 11.9 percent in 2021. Overall housing contributed 16.2 percent of GDP versus 16.7 percent in 2021. The construction industry added 231,000 jobs in 2022. Not bad.

According to our assessment, relatively low debt ratios should limit the impact of higher interest rates on the housing market and overall consumer spending. The economy remains on solid ground as a result of households’ strong financial standing.

Source: NAHB

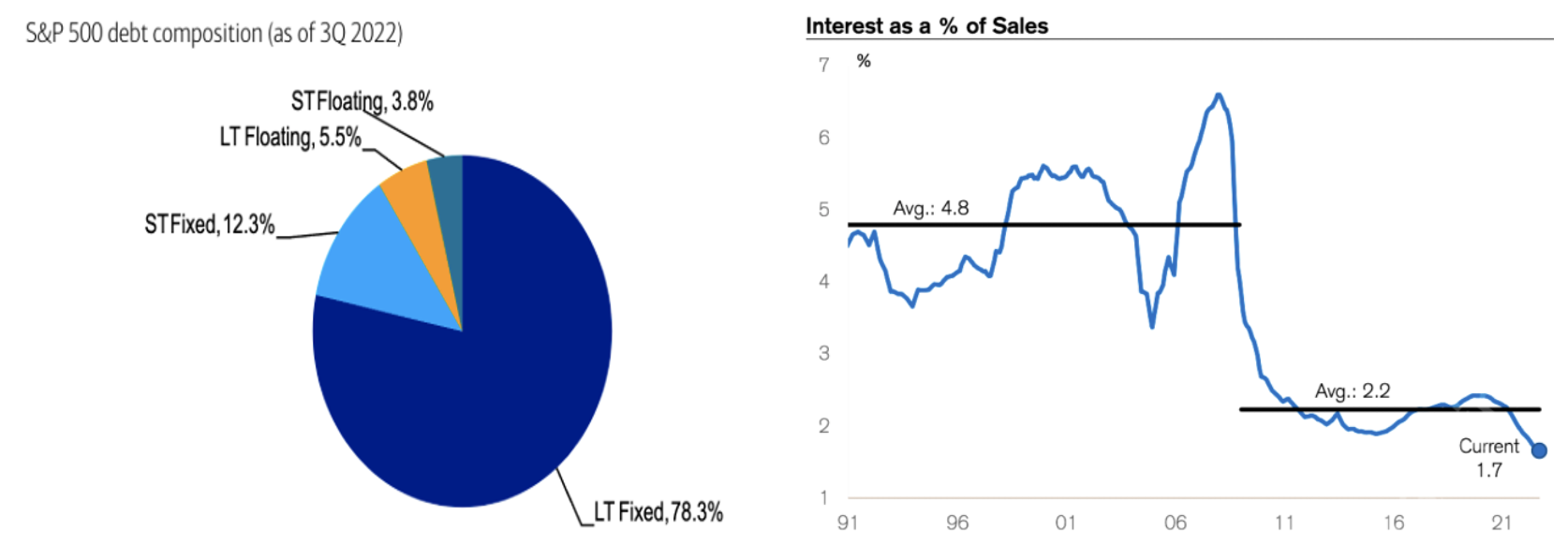

After the Great Recession, S&P 500 companies put a lot of time and effort beefing up their balance sheets. When interest rates plunged following the pandemic, they seized the opportunity to lower their interest payments and move into later-maturing debt. In 2020 and 2021, $2.27 trillion and $1.96 trillion in US corporate bonds were issued, respectively.

The average maturity of bonds issued by S&P 500 companies is eleven years today, compared to seven years in 2007, and the interest paid by nonfinancial corporates as a share of their total debt is 3.6 percent, the lowest since the late 1950s. Interest expense as a percentage of sales is historically low.

Companies are hence less susceptible to higher interest rates. Today’s share of short-term debt is lower than it was leading up to the 2001 and 2008 recessions—both of which culminated in a wave of bankruptcies. Eighty percent of debt maturing over the next year and 74 percent maturing in the next two years is investment grade. Just 8 percent of junk bonds mature over the next two years.

Despite the fastest-rate hike cycle since the 1980s, interest rates are scarcely restrictive. Only when the 10-year Treasury yield exceeds the level of nominal economic activity for an extended period of time does the economy tip into a recession. This is not a concern with nominal GDP growth running above 7 percent and the 10-year yield at 3.5 percent. Long-term borrowing costs are still manageable for companies.

Rate increases can hurt the economy more immediately when expansions are fueled by credit growth, in contrast to incomes and stimulus, which have served as the primary drivers of the post-pandemic recovery.

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse

So is it blasphemy to argue that the Fed is doing a good job and that “immaculate disinflation” is already underway? We stand by our view that inflation this year will return to levels that will be acceptable to policymakers and will do so without significant job losses.

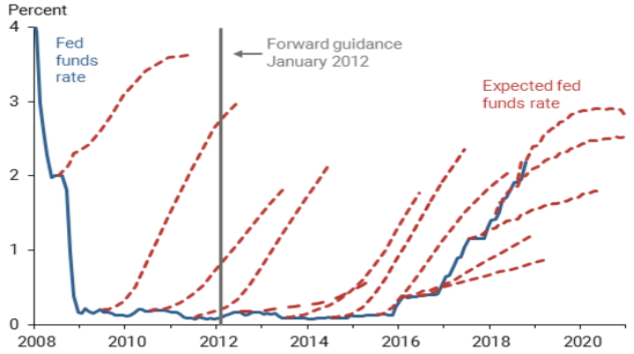

The Fed funds futures are showing six interest rate cuts over the next eighteen months. We would take the other side of that. The market is almost always wrong about what the Fed will do. Remember how investors anticipated a quick policy rate liftoff after the Great Recession?

Given the deep downturn, however, the Fed decided such an early liftoff is not appropriate. On January 25, 2012, the FOMC stated that “economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014.”

While this forward guidance helped to moderate market expectations—flattening the dashed lines in 2012, 2013 and 2014—the market’s persistently inaccurate projections of the direction of interest rates persisted.

What if the reverse happens now? Investors predicting quick policy rate cuts each year while the Fed stays on hold. The institutional memory of fighting inflation may loom large in determining the appropriate monetary policy stance. We believe the Fed will be done hiking at the next meeting but won’t cut rates anytime soon.

Source: Federal Reserve