“It’s possible that this time is really different,” Fed chair Jerome Powell observed after hiking interest rates for a tenth straight time. “It’s interesting that we’ve raised rates by 5 percentage points and the unemployment rate is even lower than where it was when we started.”

Except … wait: doesn’t it typically take fourteen months from the time the Fed starts raising interest rates until the unemployment rate reaches its lowest point and begins to rise? With the first Fed hike in March 2022, that means the unemployment rate should increase now.

Our bet is that it won’t.

In The Four Agreements, Don Miguel Ruiz counsels us to refrain from making any assumptions. “If we don’t make assumptions,” he writes, “we can focus our attention on the truth, not on what we think is the truth. Then we see life the way it is, not the way we want to see it.”

The idea that the job market will weaken is predicated on the assumption that all recessions look the same. But the pandemic-induced recession was quite different.

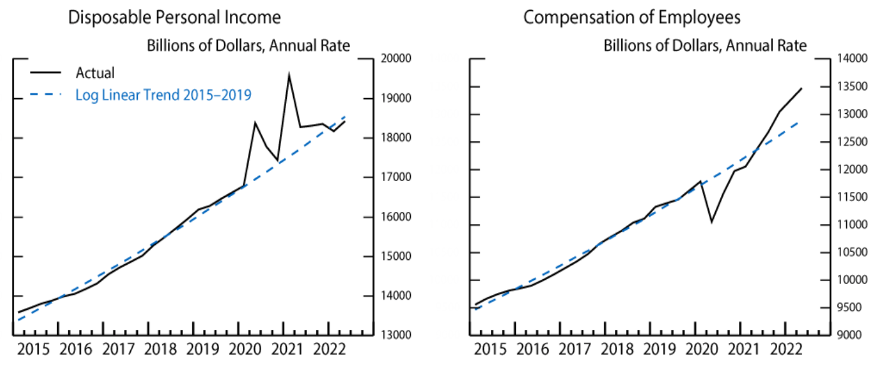

Past recessions disrupted employment from the demand side. Job losses were centered around goods-producing sectors, such as manufacturing and construction. In contrast, the pandemic disrupted labor supply, with job losses mostly in the service sector. The emergency monetary and fiscal response unleashed a positive demand shock that surpasses our understanding, even now.

Source: Federal Reserve

Whereas in the past it took years for job openings to recover, there have been more job openings than unemployed people since May 2021. The ratio of job openings to unemployed people is 1.6 and reached a record high of 2.0 last summer. The service sector, which makes up 80 percent of total employment, remains underemployed.

Aside from the tech sector, everyone is looking to hire. How can we have a labor market recession? Labor demand decreased by around 2.5 million in prior recessions. We have seen the number of job openings decline by 2.4 million so far. Given excess labor demand is still 4 million, the job market will remain tight even if growth slows.

Both new-home construction and new-car demand are vulnerable to rising interest rates, but these industries are less rate-sensitive than they were.

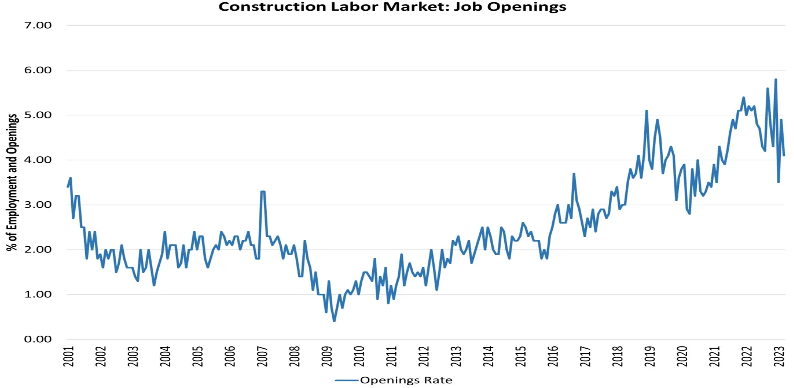

The lack of housing supply is driving demand for new-home construction despite higher mortgage rates. A record number of multifamily units are under construction, which will be ready later this year and in 2024. Notwithstanding the recession in the single-family housing market, construction employment is historically low.

“It would be difficult to identify a period during which the construction labor market was more constrained than it is now,” observes Anirban Basu, the chief economist at Associated Builders and Contractors. He estimates an additional 550,000 construction workers are needed this year.

After the mid-2006 peak in construction activity, it took another eighteen months for construction unemployment to rise in a meaningful way. The backlog is bigger today; the labor shortage is worse due to retirements and slower immigration, and if there are layoffs in single-family housing, there is offsetting demand from multifamily projects and those funded by all the infrastructure spending approved by Congress.

There are nearly twice as many job openings in the construction industry as there were in the mid-2000s. That leaves a lot of room for the housing market to weaken before it leads to a significant rise in joblessness.

Source: NAHB

Pent-up demand in the auto industry, which is still recovering from pandemic-related supply shortages, also makes it resilient to higher interest rates.

Even after increasing by 7.7 percent in April, new auto sales still sit at about one million annualized units below 2019 levels. Additionally, the inventory-to-sales ratio in the auto industry remains well below pre-pandemic levels, indicating the need to build up more.

GM underwent a global restructuring in 2019 that trimmed tens of thousands of jobs and closed factories across the country. Ford also cut 7,000 jobs that year and is eliminating another 4,000 workers from Europe, where it is only marginally profitable. Both companies are boosting their US investments and creating new jobs as they switch from making ICE vehicles to batteries and all-electric vehicles.

The manufacturing industry faced a major setback after losing roughly 1.4 million jobs at the onset of the pandemic. Since then, the industry has added 1.6 million jobs and there is still demand for nearly 700,000 more workers.

Despite the fastest monetary tightening in four decades, the distinct demand dynamics of the auto and construction industries are disrupting the patterns normally associated with a recession. Falling consumer demand precedes falling labor demand. We’re just not there yet—and likely won’t be for many quarters. Employment is going to hold up.

Historically, manufacturing has been acutely sensitive to business cycles, while services GDP has never shrunk from one year to the next between the Korean War and the Great Recession—a period encompassing ten recessions.

While business surveys show manufacturing has been contracting since November 2022, services are growing steadily. Many services businesses expect to continue hiring over the next six months. Leisure and hospitality still has fewer workers than it did before the pandemic but much stronger levels of demand.

Source: The New York Times

Every week, all eyes are on the initial jobless claims number, which has preceded every jump in the unemployment rate. In the first month of all recessions since 1970, the four-week average of claims rises to 0.3 percent of the labor force. The four-week average today is 231,000, just 0.14 percent of the labor force. It would need to rise to 466,000 for claims to reach 0.3 percent.

But what about the decline in temporary employment, the rise in continuing unemployment claims, and employees putting in fewer hours? These are just a sign of moderation after the post-pandemic boom. The US average weekly hours reached an all-time high of 35.0 hours in January 2021, and are now at 34.4, the average since 2006.

So don’t make assumptions. This time really could be different. We’re witnessing a secular tightness in the labor market.

Some may find this worrying. The logic is fairly simple: although inflation is ebbing, it’s not slowing as quickly as the Fed wants, and if the labor market remains tight, employers will be under pressure to raise wages. This could then hurt corporate margins, which is bad for stocks. And the Fed would continue on its rate-hiking journey, which would plunge the economy into a recession.

We find it encouraging. As we wrote in October 2021, “Technologies that reduce labor utilization and augment productivity will help companies operate amid labor scarcity. A global survey of chief information officers by Gartner found that more than 90 percent plan to have deployed AI technology in some form within the next three years.”

Although it is not obvious in the statistics yet, we believe an increase in automation and productivity will be an economic legacy of the pandemic. What if that keeps a lid on inflation and allows wages and profits to rise together? What if the future is not one of stagflation, but rather a new era of productivity-led growth, like the early 1950s, 1960s, or late 1990s? The timing of the AI boom could not have been better.